Female Designers in Spanish Transition to Democracy, 1982-1992:from decoration to avant garde production

Review | Revisión

Josenia Hervás y Heras1 y Silvia Blanco Agüeira2.

1Department of Architecture, University of Alcalá de Henares, Plaza San Diego, s/n 28801 Alcalá de Henares (Madrid), jhervasheras@colaboradorst.es, ORCID: 0000-0001-7312-7975

2Department of Architecture, CESUGA, Rúa Obradoiro, 47, 15190 A Coruña, sblanco@usj.es, ORCID: 0000-0001-9409-7269

Received: 20 March 2021 | Accepted: 02 May 2021 | Published: 29 June 2021

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25267/P56-IDJ.2021.i1.5

From decoration to interior design

On 14 May 1998, an exhibition with the title "Industrial Design in Spain: a Century of Creation and Innovation" (Figure 1) was inaugurated at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. More than three hundred objects were documented in the exhibition’s catalogue, most of which were either recorded as being made by men or by companies where the authorship was not specified. Only one design made exclusively by a woman was listed; while another, was created by two women and fifteen pieces were created by collectives, with at least one female name featuring in the description. Similarly, Giralt-Miracle, Capella and Larrea (1998) have found that female authors only appear from 1973 onwards, and only three female architects, Beth Galí (Barcelona, 1950), Carme Pinós (Barcelona, 1954), and Olga Tarrasó (Navarrés, 1956), appear in the list, and generally, there is hardly any variety in the participation of female designers compared to men, of whom generally several objects are exhibited.

Figure 1. Poster and cover of the exhibition "Industrial Design in Spain, 14 May - 31 August 1998".

The exhibition was divided into five sections, ranging from 20th century precedents to the internationalisation of Spanish design. There are no references to women in the "Precursors and proto-design: 1900-1929", nor in the "First proposals: 1930-1959". With the passing of Decree 2127 of 24 July 1963 on the regulation, among other matters, of studies in industrial design, draughtsmanship, decoration and advertising art, a greater presence of women should have been expected in subsequent decades, given the more encouraging environment. However, their inclusion is still insignificant, with only the names of Anna Bohigas and Mireia Riera appearing in the catalogue. Anna Bohigas appears together with Lluis Clotet and Oscar Tusquets, in the Hialina bookcase (1973) and in the BD Extractor Hood (1978). Mireia Riera is recorded in the company of Pep Bonet and Cristian Cirici, with the Seville Chair (1974).

Women creators would become more obviously involved with scientific and technical progress and consumer demand in the following decades. The chapter "The boom in Spanish design: 1980-1989" records Gemma Bernal (Eclipse Table, 1984, with Ramón Isern), Beth Galí (Aalta Lamp, 1984, with Marius Quintana), María Luisa Aguado (Macaya Wall Lamp, 1986, with Josep María Julià), Carme Pinós (Sitting Chair, 1988, with Enric Miralles) and Olga Tarrasó (P.E.P. Street Lamp, 1988, with Jordi Heinrich). As for the section "Standardisation and internationalisation: the 1990s", the names of Montse Padrós, Jeannette Altherr, Ágatha Ruíz de la Prada and Carmen Menchón are documented, and Gemma Bernal joins them once again. It is striking that a final appendix of the catalogue only features male artists; that no design by Lola Castelló appears, only one by her partner Vicent Martínez; or that no mention is made of the textile designs of Nani Marquina, although an anti-drip oilcan designed in 1961 by her father, the architect Rafael Marquina, does appear.

The historiography of Spanish design is fed by texts and other documents (Bermejo and Larraya, 2019), which continue to treat creation as a male preserve, overlooking the fact that the first Spanish female designers who achieved fame did so mainly in textile, graphic and interior design, fields quite removed from more technical fields such as industrial design (Ramírez, 2014). Even in the sixties, interior design was considered one of the few job opportunities available to women who wanted to study after general education and high school. At the time, the term interior design was not used, they were called decorators because they studied interior or exterior decoration, a feminized profession. Decorating is not exactly the same as creating or designing spaces. According to the Spanish Royal Academy, it is defined as "to adorn, to try to embellish a thing or a place". That is precisely what they were expected to bring, the concept of adornment or beauty, which at that time was thought of as the "feminine touch".

In Germany - with the Bauhaus as a reference and later the Ulm school - women had been trained since the twenties to design textiles, lamps, furniture, kitchenware and utensils, or in advertising or graphic design. In Spain, during the first half of the 20th century, the subject of furniture and lighting was in practice left to architects and any industrial design was centred on motorcycles, assault rifles, staplers, table football or refrigerators. In the sixties, and up until the mid-seventies, as Spanish society developed, other creative fields opened up; but based on the maxim that design is the expression of a country's culture, society and industry, this opening up inevitably was to the advantage of men. In 1960 the Industrial Design Association, ADI-FAD, was founded in Barcelona, whose main driving force since its creation has been the Delta Awards, a platform for public recognition of the work of both industrial designers and manufacturing companies. Since its first edition in 1961, there has been a gender imbalance among the winners, with only the names of María Rosa Ventós (1961) and Mireia Riera (1975) standing out in the early years.

For all these reasons, the first Spanish women designers had to struggle in a country where their rights as free citizens, independent of their fathers, brothers or husbands were not legally recognized. It was not until the spring of 1979, when the first democratic Chamber of the Congress of Deputies was constituted, that Spain and Spanish design began to take off. Nor should we forget that at that historic moment, there were only fathers of the Constitution, although twenty-seven women in a total of seven hundred senators and deputies, defended the civil rights of the women and men of the country they represented. From the eighties onwards, culture, society and industry had other objectives and women knew how to grasp and take advantage of them. The apparently inconsequential decision to modify their cataloguing, from decorators to interior designers, enabled their conversion into avant-garde designers, producers, businesswomen and disseminators.

The examples of Lola Castelló (1947) and Nina Masó (1956) serve as examples of this metamorphosis during the years of the Spanish transition. Both initially studied to become what was then known as professional decorators, although they always felt they were product and interior designers. Their professional and business careers show us the progression through different facets within the field of design, from the importance of the dissemination of ideas to the difficulty of mass production.

Lola Castelló: collective design and the professionalism of a businesswoman

Lola Castelló (Aielo de Malferit, Valencia, 1947), began studying what was then known as interior decoration at the Barreira Studies Centre, graduating in 1970 from the School of Applied Arts and Artistic Trades in Valencia. She remembers her student days - between the end of the sixties and the beginning of the seventies - as a mostly feminine environment, although this aspect did not translate into a greater inclusion of women in professional practice:

Back then they were not called design or interior design studios. In the School of Applied Arts we had as specialties draughtsmanship, decoration or advertising design. That's where I met Vicent Martínez. I was in decoration and he was in advertising. In decoration, which would now be interior design, many women were studying, but then they fell by the wayside, their presence was not reflected in professional practice, it was all related to the society of that time. (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

During her childhood, the first pieces of furniture that caught Lola Castelló's eye were the chairs, armchairs and rocking chairs made by the firm Thonet, which she found in her grandparents' house. She played more at fitting out spaces for her dolls than at playing with them, making houses or furniture out of clay in the backyard, taking up her brothers' architecture and construction games and even daring to move the furniture around in the family home. When she started to get involved with industrial design, her female references were Ray Eames and Sonia Delaunay (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

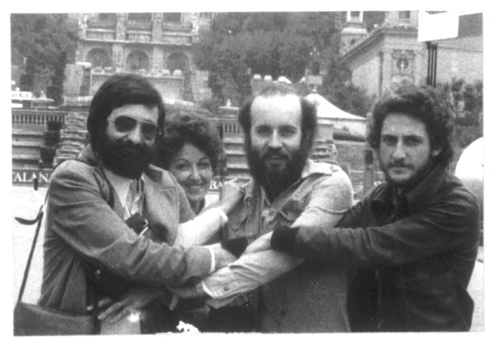

Castelló was a pioneer in experimental design ideas from collective work. In this sense, her work was shaped by events during the last years of Franco's regime in the Valencian Community, when industrial creation took on a communal form. In 1973 NUC was born, set up by Daniel Nebot, Vicent Martínez along with Lola Castelló, with Luis Adelantado acting as agent, contacting the manufacturers and participating in the decisions they made about the designs (Figure 2). In 1984 the group Triseño emerged, formed by Gemma Furió, Anna Gutiérrez and Gabriel Folqués. That same year the collective La Nave was created, active from 1984 to 1991, which brought together the most avant-garde industrial and graphic design, marking the beginning of Valencian design and providing the seeds for the Association of Designers of the Valencian Community. It comprised professionals from various disciplines, with an interest in covering all fields, from architecture to graphic or industrial design, and had a notable female presence in its ranks, including Marisa Gallén, one of the founders of La Nave. Sandra Figuerola and Anna Gutiérrez were also members of the group. Through their collaborative work, these women were able to gain entry to the profession, and dedicate themselves more fully and with greater confidence and stability to their industrial design work.

La Nave became a symbol of modernity. We were into coworking 'avant la lettre'. We came together to have more space and possibilities than we would have had working individually. Some projects were done as teams, but basically, we shared a space and a philosophy. We were a diverse group and we all learned a lot. (Zafra, 2019).

Figure 2. NUC Group. Lola Castelló, Vicent Martínez and Daniel Nebot. Barcelona, ca 1974. Luis Adelantado, who also appears in the group photo, acted as a kind of agent, contacting manufacturers and participating in the decisions that the group made about the designs. Photograph provided by the Valencian Design Archive.

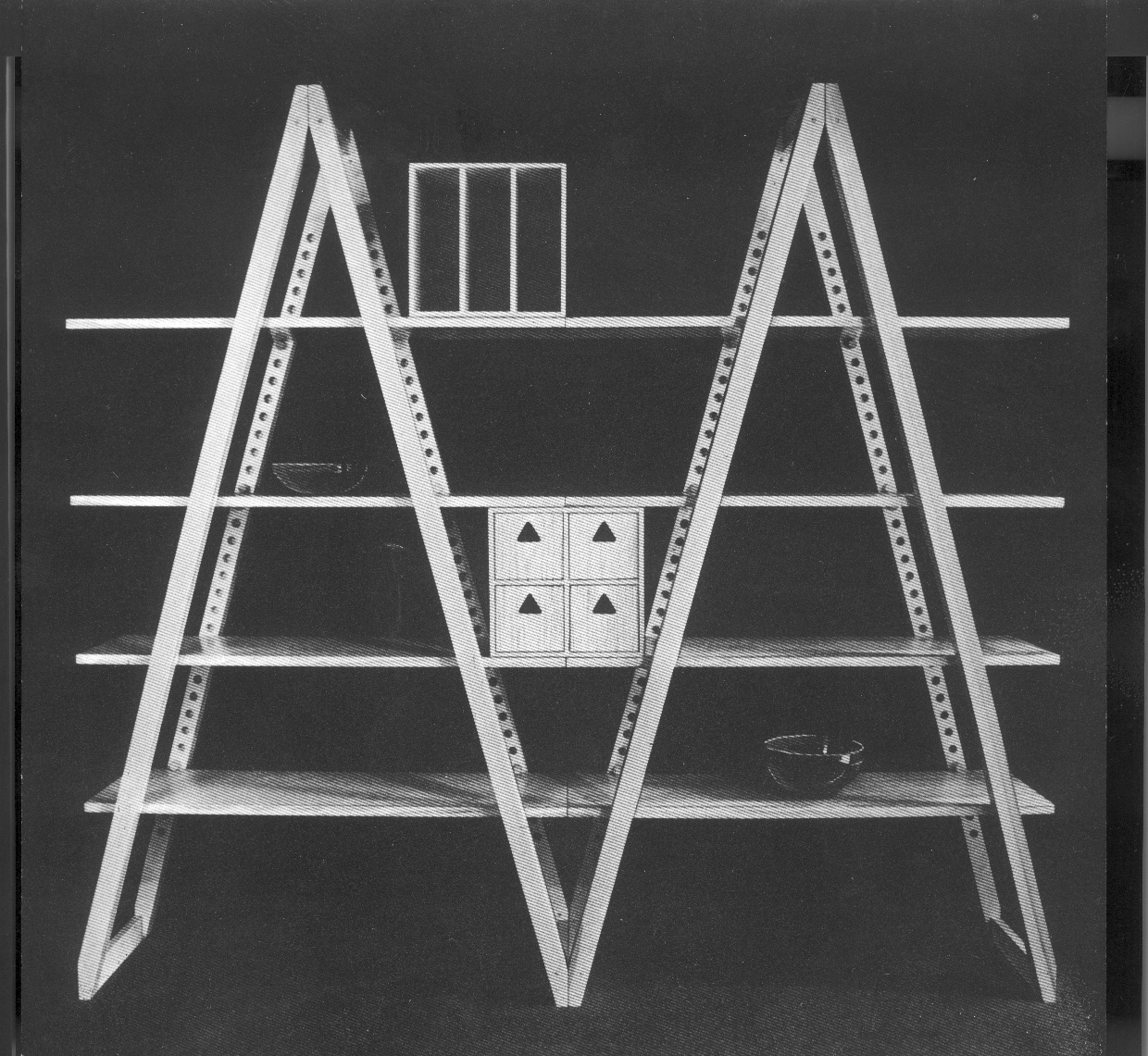

In the nineties, these groups redirected their experimentalism towards productivity, the competitive factor and the professionalization of design, which led to some leaving and others to change. Lola Castelló, who during her time with the NUC group had created a range of children’s furniture called Trilátera (Figure 3), continued to focus on the collaborative nature of product design:

Product design starts by deciding on the product to be made, in consultation with the sales department. From there, we work with the idea in product management, then, it is realized with the prototyping department and from these three departments, the final product is created. This way of working has been very rewarding for me. You always learn from others. (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

Figure 3. Lola Castelló. Children’s furniture collection Trilátera, 1974. Valencian Design Archive.

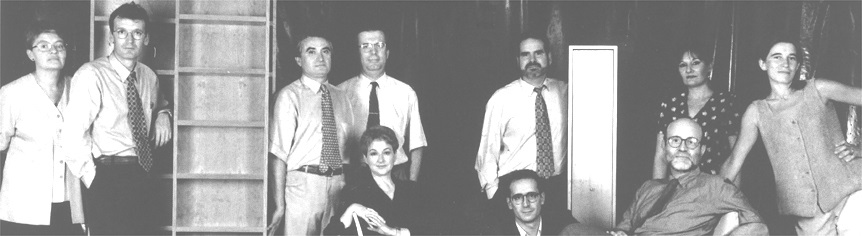

After the dissolution of the NUC group, Lola Castelló founded the company Pam i Mig with Vicent Martínez and a third business partner, which primarily made pine wood furniture. After a financial crisis that led to the departure of their partner, Castelló and Martínez bought part of the company, which led to the birth in 1980 of Punt Mobles (Figure 4). Thus, the dynamic pace of the industry drove this creative Valencian to combine the roles of designer, interior designer and businesswoman, which was a real challenge for her:

In Punt Mobles I worked in product design, as an interior designer in installation projects or creating stands for the fairs we attended, and as a businesswoman, in customer relations and in the sales team. We went to many fairs in a charter flight full of men, there were very few women, sometimes only me and a lady who sold antique furniture. (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

Figure 4. Management team of the company Punt Mobles. Photograph by Concha Pradas.

Among Castelló's most outstanding creations we can mention the table Papallona (1991) or the chair Brava (1992). The table allows, through the hinging of the tabletop (Figure 5), to carry a metaphorical meaning: the table flaps open and close in the same way as the wings of a butterfly fold (Rambla, 50). The chair (Figure 6) is defined by its rounded and smooth edges. The work process was always the same, once the sketches, the elevation and the profile were drawn, she continued on to the details, defining the upholstery to the colours. The result is the illustration of essential ideas, executed using quality materials such as wood, which still retain their original refinement and subtlety after so many years. Her training as an interior designer gave her a feel for the practical and aesthetic side of design, the control of function and form, although it did not provide her with the rudiments of mass production, which she had to learn during her immersion in the professional world. Nevertheless, she has been able to apply her creative genius to commercially successful products, with warm and even sinuous lines (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Lola Castelló and Vicent Martínez. Table Papallona, 1991. Photo Globus, 1999. Valencian Design Archive. | Figure 6. Lola Castelló. Drawing Silla Brava, 1992. Valencian Design Archive.|Figure 7. Lola Castelló. Armchair Ritmo, 1989. Valencian Design Archive.

From out of the industrial boom of the nineties, other women product designers emerged to occupy a prominent position in the Valencian scene. Such is the case of Mariví Calvo, born in 1960, who after studying History of Art and Fine Arts, in 1995 - together with Sandro Tothill - set up the company Lámparas Luzifer, dedicated to the manufacture of these light fittings made from sheets of wood. However, Catalonia had a greater workforce, as design is usually linked to the development of industry. In fact, pieces by the Catalan artists Nani Marquina, Gemma Bernal, Nancy Robins, Margot Viarnès and Ana Mir; the Madrid artists Marre Moerel and Eva Prego; and the Valencian artists Mariví Calvo and Lola Castelló, were brought together for the collective exhibition ¡Mujeres al Proyecto! organized in 2007 by AECID, the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation, and curated by Marcelo Leslabay, who said after being interviewed by the digital newspaper Canarias ahora (2007):

Now things are changing and in various industrial sectors such as automobiles, household appliances and telephony, marketing departments have detected that with the increase in women’s purchasing power, consumer trends have also changed, as when buying a product women are more demanding than men. This phenomenon has caused many European companies to hire female designers to develop their future projects, because if they meet women’s requirements, they will also meet those of men.

When asked if she had ever felt disadvantaged in her professional work, because she was a woman Lola Castelló replied that she hardly ever felt discriminated against: "Just a few small slights" (Castelló, personal interview, 2021). When asked about the moment when Punt Mobles received the National Design Award in 1997, she remembered it vividly: "The award was presented to us by the King and Queen of Spain at the Palacio de la Música in Barcelona and I went up to the podium with my partner Vicent Martínez. He was the one who collected the award" (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

The following year, in 1998, the exhibition catalogue for "Industrial Design in Spain" defined Punt Mobles as a "company created in Valencia in 1980 by the designers Vicent* Martínez and Lola Castelló", later clarifying the asterisk over the name of her partner at the end of the paragraph, in which it was stated that he was the recipient of the National Design Award in 1997 (Giralt-Miracle et al, p. 420). In the documentary Función y Forma, made by Televisión Española, and focused on the subject of Spanish design (Román, 2016), numerous designers were interviewed, including Martínez, with the subtitle: "Vicent Martínez (Punt Mobles). National Design Award 1997". There was no reference to Lola Castelló.

Lola Castelló (Figure 8), who has combined her work as a designer with that of commercial director at Punt Mobles, has also been involved in teaching, which has allowed her to appraise the changes that have taken place in the industrial design scene over recent decades.

In Valencia we had several schools: the Barreira School, the Peris Torres School and the EASD. In the School of Architecture also there were very few women. Before we had a school in Valencia, they were going to Madrid or Barcelona. I met professionally the architects Fátima de Ramón, Gema Martí and Cristina Grau, as well as the architectural historians Pilar Inchausti and Trini Simó. […] All this changed a lot in the nineties. I taught Design at CEU San Pablo University from 1990 to 1997. As the studies were more technical, the number of male and female students was more even. Here it was already noticeable that the girls were staying in the profession more (Castelló, personal interview, 2021).

Figure 8. Photo of Lola Castelló, with some models of her designs. Valencian Design Archive.

Nina Masó: design, manufacturing and production

Nina Masó (Barcelona, 1956) states emphatically that she never had a family link with design: "I loved to draw, I have been obsessed with interiors since I was a child. When I finished my regular studies I opted for secretarial work, which was very typical at the time" (Masó, personal interview, 2021). Certainly, in the sixties and seventies, there were some professions that were considered suitable for women: secretary, nurse, teacher or decorator. Since the twenties, women’s physical aspects continued to be used as a recurring argument when it came to assessing suitable activities, whereby interior design and decoration were considered as permissible because of their markedly feminine character (Cabello, 1921). In fact, gender-segregated schools were created, such as Elisava, founded in Barcelona in 1961, which began by teaching kindergarten-related studies, before becoming the first design school in Spain (Pacheco, 2016).

Nina began her decoration studies in 1974, and after their completion entered into partnership with two other colleagues, combining her work with window dressing, advertising or assembling stands for fairs, where she was fully aware that she was moving in a man's world. In 1981 she met Gabriel Ordeig Cole, of British origin and training , who made lamps to order. Architects and interior designers asked him for unique designs for entertainment venues that he achieved by playing with the lamp shades as a coloured canvas, providing a warm, comfortable and distinctive touch. They became a couple, both personally and professionally, collaborating in decoration and interior design projects in bars and venues as well known as Cibeles, Boliche or Café del Sol. Many of these lamps have become design icons, endlessly copied, as was the case with the GT4, initially designed in 1983 for the Sísísí bar (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Nina Masó and Gabriel Ordeig. GT4 Lamp, designed in 1983 for the bar Sísísí, in Barcelona.

That's how we fell in love, being personal and professional partners. I moved on from the partners and friends stage and I started to collaborate with Gabriel doing interior design. The lamp Sleeping Beauty, designed by Gabriel was very successful. We concealed the fluorescent tubes and the shade was the main focus. Seven artists collaborated by silk-screening different prints. I have seen in sites where I am also attributed as author, but the truth is that I was only advising him on the chromatic theme, the choice of colours. (Masó, personal interview, 2021).

In 1984, Nina Masó opened her own home decoration shop in a small house in Cardedeu (Barcelona), the town where her parents lived and where she spent her summers. Thanks to the shop, called Paspoc, in which her mother was also involved, she began to manage the sales channels and product distribution, giving rise to a potential partnership to provide funds to expand the company. Thus Santa & Cole was born in 1985 (Figure 10):

My sister had married Javier Nieto Santa, who was a businessman and came from the publishing world. He talked to Gabriel and me about joining us and we started to think of names. We considered Manufacturas Barcelona, among other possibilities. Then Javier saw that their mothers' last names were Santa and Cole, one in Spanish and one in English. It sounded great, Spanish and English was what we were looking for, they were distinctive sonorous and international. My second surname, Agustina, was not so sonorous and distinctive. We all liked it and I always was and am the "and" that united the group .

Figure 10. Nina Masó, Gabriel Ordeig and Javier Nieto in 1987. First headquarters of Santa & Cole in Santísima Trinidad del Monte street, Barcelona.

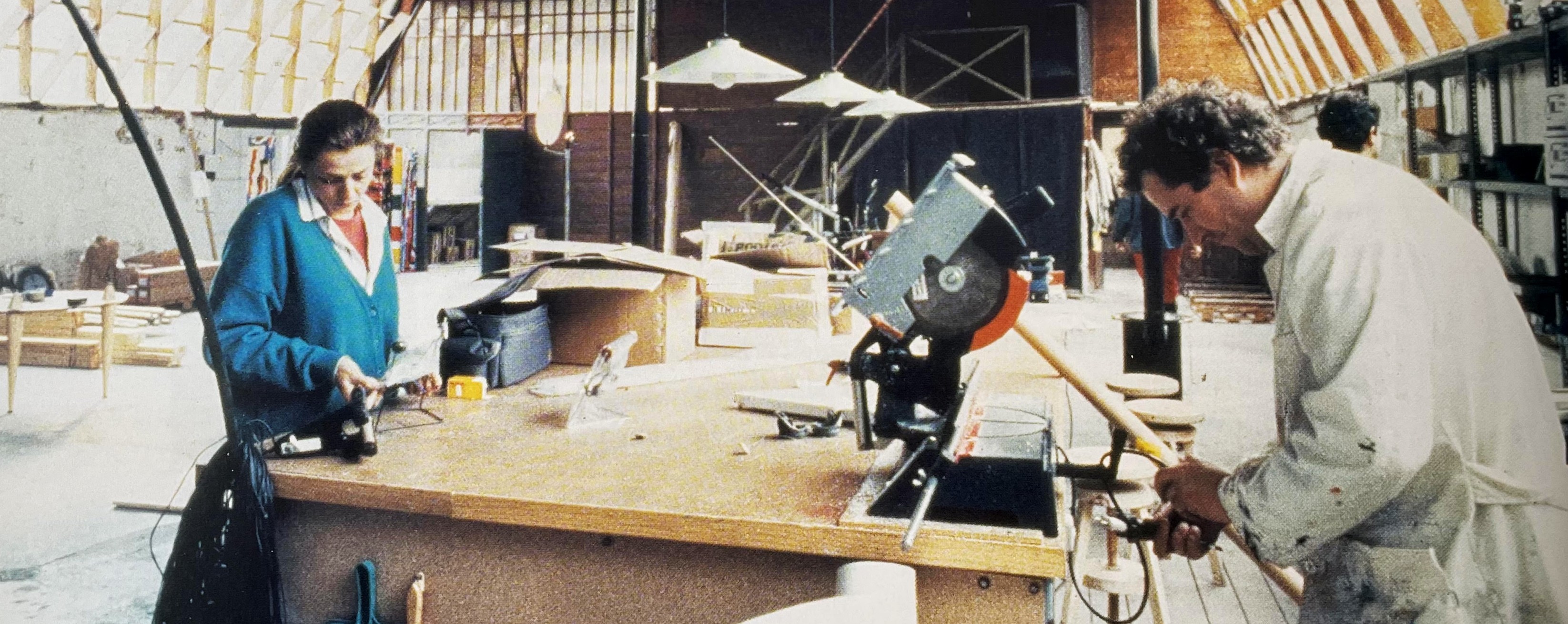

If before the creation of Santa & Cole, Nina Masó was in charge of interior design tasks, as she mastered drawing and illustration, her functions did not change much afterwards, where Gabriel Ordeig continued to provide an artistic perspective (Figure 11):

Javier Nieto Santa wrote the texts, he was the writer; Gabriel Ordeig was the artist, and I, as an interior designer, had a different vision of industrial design. I see the context. The image is from me. Gabriel died in 1994 and Javier and I continued to head the company, although around 2005 I left Santa & Cole for two years due to a few quarrels, but they missed me and I came back. Currently, I am product designer, I have very good young people in my charge; there are already many girls and boys in their twenties and thirties working with us. (Masó, personal interview, 2021).

Figure 11. Nina Masó and Gabriel Ordeig working on the first prototypes of Santa & Cole, 1987 (Folch and Serra, 2004, p. 62).

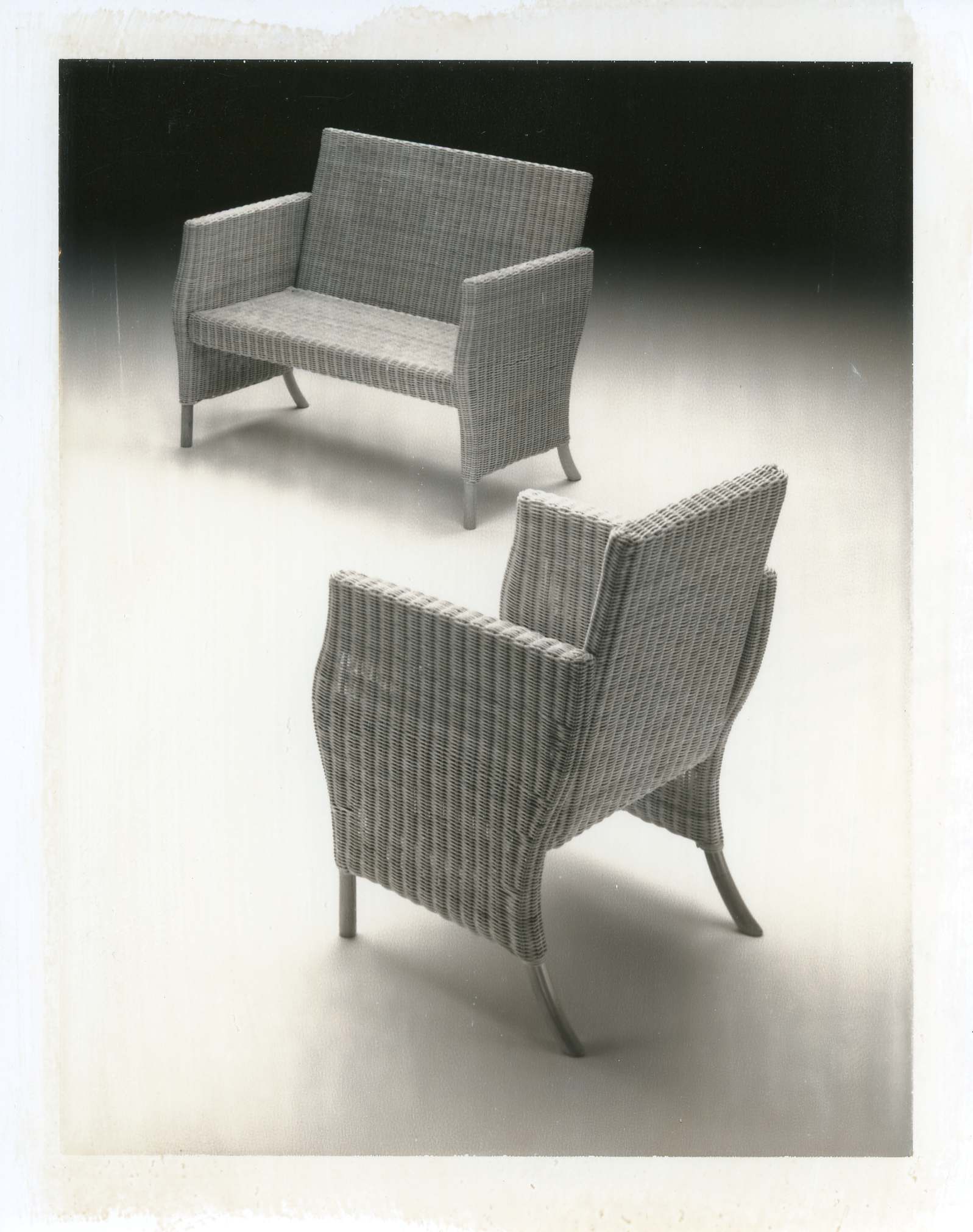

Regarding the founding partners, Masó believes that their success was based on each having a very defined role. Their success allowed them to collaborate and work with renowned professionals and stand out in the field of industrial design where it was not easy to find women. However, some names immediately emerge, especially in Catalonia, where Gemma Bernal began working in the sixties, collaborating with numerous manufacturing companies. Winner of the Delta de Oro ADI-FAD prize in 1969, she worked until 1988 with the industrial designer Ramón Isern. Nani Maquina, who in 1987 launched her own brand for the design, creation and distribution of carpets, stands out as a businesswoman. In contrast, Mariona Raventós with Jordi Miralbell formed a couple who were interested in craft design and the treatment of materials, texture and colour. Since the end of the sixties, they have created a catalogue of handcrafted furniture and domestic lighting. Trained at the Elisava School in Barcelona, they collaborated actively for more than fifteen years with Santa & Cole as authors, editors and partners.

Some of the first active designers were foreigners. Figures such as Nancy Robbins, an American interior designer, born in Michigan, who in 1984 opened a furniture shop in Barcelona in her name and began to work as a designer. The German Jeannette Altherr settled in 1989 in Barcelona to complete her training, after studying design in Darmstadt, founding the studio Altherr Lievore Molina in 1991.

Also renowned for their furniture and product designs are the architects Beth Galí (Barcelona, 1950) and Carme Pinós (Barcelona, 1954), both graduates of the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona. Galí graduated in 1991, after having studied industrial design at the Eina School; Pinós qualified in 1979, working first in collaboration with her partner and husband, Enric Miralles, and from 1991 onwards solo, under the name Estudio Carme Pinós .

Another figure worthy of note is Mireia Riera, who was a pioneer in Barcelona's avant-garde scene, supplying products that provided functional solutions. Together with Anna Bohigas -interior and product designer-, Oriol Bohigas, Miguel Milá, Oscar Tusquets and Lluís Clotet, among others, Riera helped to bring together a group that developed innovative furniture and accessories. The project, which was renamed in the 1970s as Bocaccio Diseño (BD), aimed to produce and disseminate contemporary design. The group’s main aesthetic influences came from Milanese architects, but they also drew inspiration from the great European pioneers, turning their daring solutions and re-editions of iconic pieces into the signature image of the company. When the products were eventually distributed outside Catalonia, the furniture house’s sales outlet in Madrid had three women at the helm: initially Belén Feduchi and Isabel Lantero, and later Luz Sánchez Muro. Thus, when BD Madrid opened its doors in 1977, in the heart of the Salamanca district, it sparked a female-led attempt to edify the public about avant-garde furniture.

Nina Masó has always leaned towards suggestive objects that provoke emotion in the viewer. She is attracted by fine materials, the handmade process, the care of the finishes and the colour. It's all about evoking emotion with sobriety and attention to detail. Her aim is to generate desire, not trends, without giving special prominence to the creator, whether male or female: "I would never create an object that I wouldn't want to have at home." As a pioneer in the implementation of LED light fittings Santa & Cole's designs are enjoying a comeback, after their redesign. Masó is responsible for the choice of the colour nude for a reedition of the lamp Maija, originally conceived in 1955 by the Finn Ilmari Tapiovaara. She continues to strive after warmth in all types of lighting:

Now I am very happy with an edition of candles by Marre Moerel, a Dutch designer based in Madrid, a city that I would now almost say is above Barcelona in terms of design. My hopes rest in the generation in their thirties, I connect very well with all of them. (Masó, personal interview, 2021).

Nina Masó is image and therefore illumination. Her work comes from a fascination with the magical and mystical properties of light, in tune with the research of the German designer Ingo Maurer, whom she deeply admired: "I remember his creativity, his genius and what a wonderful person he was. He was a poet of light, a visionary. The first to move forward with new technologies". (Masó, personal interview, 2021).

Conclusions

The professional careers of Lola Castelló and Nina Masó acted as a creative engine when it came to overcoming challenges and laying the foundations of female creation in the field of industrial design in Spain. But they have not been the only ones who have explored new techniques in search of innovative and functional pieces. Their capacity for collaborative work is amply demonstrated, at a time of cultural effervescence and excitement in the face of Spain’s new democratic turn. For this generation of female creators, who graduated in the seventies, the lack of local models to follow turned foreign women into the mirror in which to regard themselves. Nor was there ever a Spanish Werkbund, a nationwide organisation that brought together professionals from the world of design, art, architecture and engineering to cooperate with the country's industries. It is not surprising therefore that Lola Castelló - one of the pioneers in furniture design in Spain -, cited Sonia Delaunay, together with Ray Eames, as her influences.

The work of Spanish women designers, who failed to make the impact they merited, as they were initially looked upon as decorators, aroused new interest between 1982 and 1992. Yet, avant-garde design had, in its tasks of dissemination, marketing, operational management and image, a markedly feminine character. It is therefore not such a bold claim to say that the eighties marked a new era for both female designers and architects in our country. They were able to participate in projects with their colleagues and new avenues of work were opened up for them, alone or accompanied. By appealing to the buyer by using seduction or desire as priority objectives, they opened up a new dimension to projects by combining creative genius with commercial solutions. Their work in the areas of furniture, lighting, accessories and textiles should make them a reference for future generations. Contrary to the contention of the documentary "The man who designed Spain", which focuses on the career of the well-known designer and sculptor Cruz Novillo (Bermejo and Larraya, 2019), women also helped to shape events in Spain at a very specific moment in its history.

Acknowledgements:

This article was made possible thanks to the collaboration of Lola Castelló and Nina Masó. We would like to extend our thanks to Rosa Castell Centeno, from the Valencian Archive of Design, who has provided the illustrations of Lola Castelló

Grant

This article is a result of the research grant "Women in (Post)Modern Architecture Culture, 1965-2000" (Grant Code: PGC2018-095905-A-I00) funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Spanish Government and the ERDF fund of the European Union.

Referencies

Anonymous. (2009). El diseño es función y forma. Lola Castelló. Di* (10), 6-14.

Anonymous (31 July 2007). La Regenta extends the exhibition of "Mujeres al Proyecto" until August 19th. Canarias ahora. Consulted at: https://www.eldiario.es/canariasahora/cultura/regenta-prolonga-exhibicion-mujeres-proyecto_1_5609534.html

Bermejo, A. G. and Larraya, M. (direction and script). (2019). El hombre que diseñó España (documentary). Spain: Llanero Films.

Bernal, G. et al (2007). ¡Mujeres al Proyecto! diseñadoras para el hábitat. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain: Gobierno de Canarias.

Cabello, L.M. (1922). The X International Congress of Architects. Arquitectura (43), 421-431.

Folch, B. and Serra, R. (2004). Gabriel Ordeig Cole. Barcelona: Santa & Cole/ETSAB.

Giralt-Miracle, D., Capella, J. and Larrea, Q. (1998). Diseño industrial en España. Madrid, Spain: Ministry of Education and Culture.

Pacheco, L. (11 May 2016). La casa del diseño. El periódico de Catalunya. Consulted at: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20160511/historia-escuela-elisava-rambla-ciutat-vella-5123065

Rambla, W. (2005). Vicent Martínez o el diseño de mobiliario en el marco de PuntMobles. Castelló, Spain: Jaume I University.

Ramirez, P. (2014). The pioneers of industrial design in Spain. i+Diseño: international journal of research, innovation and development in design (9), 81-94.

Román, B. (director) (2016). Función y Forma. Diseño en España. Medio siglo contigo (documentary. Spain: Rtve/La Chula Productions.

Zafra, I. (12 November 2019). Marisa Gallén, Pionera de modernidad, Premio Nacional de Diseño. El País. Consulted at: https://elpais.com/cultura/2019/11/12/actualidad/1573568215_659297.html