Diseño centrado en el usuario aplicado a una luminaria

Introducción

Este trabajo se centra en el diseño y desarrollo de una luminaria que satisfaga las necesidades y expectativas del usuario aplicando una metodología de Diseño Centrado en el Usuario. Esta permite acercarse a las personas para ofrecer un producto final adaptado a las necesidades del individuo. Así, la luminaria se enfoca en una audiencia cuyo perfil es el adulto de corta edad, entre los 20 años y los 30 años, en plena transición hacia la adultez. Por lo general y como recoge das Dores Guerreiro y Abrantes (2004), este proceso se caracteriza por tener dos dimensiones. Una primera centrada en vivir experiencias y aventuras sin grandes compromisos, y una segunda hacia la madurez basada en la responsabilidad y la estabilidad. Si bien esta investigación se centra en la sociedad portuguesa, la cercanía geográfica e histórica con España permiten considerar los resultados extensibles al país vecino. Aunque los investigadores Amichai-Hamburger y Vinitzky (2010) concluyeron que el uso de las redes sociales depende de la personalidad, su trabajo confirma la innegable tendencia de llevar las relaciones e interacciones hacia el mundo digital y online, dando a las redes sociales gran valor en el desarrollo de su día a día.

Por otro lado, cuando se habla de actividades nocturnas, queda implícito el uso de la luz, ya sea directa o indirectamente y siendo tan importante esta como sus características. Sin embargo, muchas veces hay que adaptar los medios disponibles a las necesidades de cada individuo. Un ejemplo de ello es el uso de luminarias para funciones que no son para las que fueron diseñadas a priori.

Por tanto, elegir la luz adecuada para una tarea es importante. Mientras que la luz blanca ayuda a concentrarse, la luz cálida permite crear ambientes más distendidos (B Li, QY Zhai, JB Hutchings, MR Luo y FT Ying, 2017). Hay infinidad de opciones, pero ¿cuál de todas ellas es la que realmente necesita el usuario? La respuesta a esta pregunta hace años habría salido directamente del cuaderno de dibujo, sin siquiera preguntarse si es buena idea desde el punto de vista del usuario que va a usar la lámpara. No hay que buscar demasiado en Internet para encontrar numerosos productos, servicios o ideas que fueron lanzadas al mercado y que fracasaron estrepitosamente poco después porque no se hicieron esa pregunta.

Este fue el caso, por ejemplo, de las “Google Glasses”. Este producto del famoso buscador salió a la venta en 2013 como una novedosa aplicación de la tecnología en la industria de la moda. No presentaba ningún problema desde el punto de vista técnico. Sin embargo, sí generaba conflictos en torno al usuario. Como explican Klein, Sørensen, Sabino de Freitas, Drebes Pedron y Elaluf-Calderwood (2020), el producto se planteó como una solución en busca de un problema que resolver. Por ello, este no solo chocó con la apariencia que generaba llevar las gafas puestas. Los diseñadores no explicaron claramente cuál era el propósito del producto, creando entre la población una confusión relacionada con el uso de los datos recolectados y la falta de consentimiento por parte del usuario indirecto.

Hoy en día se han desarrollado muchas metodologías y distintas herramientas para aproximarse al usuario final, para empatizar y conectar con él, para conocerle. Algunos ejemplos son el “Google Design Sprint” y la metodología Standford sobre el “Design Thinking” (Meinel, Leifer y Plattner, 2011; Mendonça de Sá Araújo, Miranda Santos, Dias Canedo y Favacho de Araújo, 2019).

Con este mismo objetivo surge el Diseño Centrado en el Usuario (DCU) en la década de los 80. Este enfoque basa sus diseños en los hallazgos de una investigación centrada en el usuario, involucrándolos y diseñando para ellos (Gladkiy, s.f.; Baek, Cagiltay, Boling y Frick, 2008). Para introducirles en la fase de investigación basta con elegir unas técnicas en las que se observe, aprenda y pregunte al usuario de diversas maneras. Ser capaz de analizar toda esta información es clave para poder plasmarlo posteriormente en el diseño de productos. Por tanto, el DCU se considera empático, porque presta especial atención al usuario; e iterativo, porque el proceso de diseño puede seguir adelante y/o retroceder, recogiendo y analizando la información recolectada tantas veces como sea necesario. Además, en esta metodología la retroalimentación es un elemento muy importante (Gladkiy, s.f.).

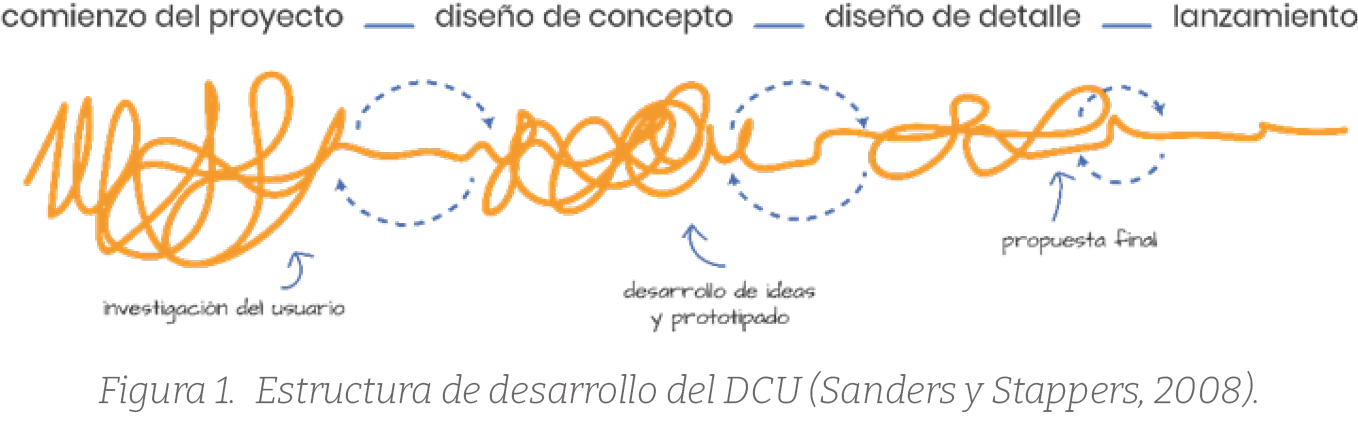

Conocido el contexto en el que se trabaja, hay que establecer los requerimientos, esto es, las necesidades, deseos, miedos, etc. Este proceso de diseño se caracteriza por ser difuso al principio, esclareciéndose según avanza la fase de investigación y diseño (Sanders y Stappers, 2008), como se muestra en la Figura 1. Tras la investigación, se crean las soluciones de Diseño adhiriendo a las especificaciones propias de los usuarios, la viabilidad económica y tecnológica. Los últimos pasos del DCU son la evaluación y su implementación.

En la primera fase de investigación, el trabajo se centra en comprender y analizar al usuario. Los hallazgos de esta etapa del proceso de diseño serán los que permitirán crear un producto o, en este caso, una luminaria que se acoja a las necesidades y deseos del usuario. La fase de investigación incluye no solo la comprensión del usuario, sino también del producto. Así, se obtiene una imagen completa del contexto. De este modo, se combinan una serie de herramientas y técnicas tradicionales y creativas con el objetivo de conocer sus hábitos, interacciones y problemas en relación a la luz.

Metodología

Con el DCU como metodología de referencia, este apartado recoge y detalla las diferentes herramientas empleadas en este caso práctico. Con el fin de aproximarse y conocer en profundidad al usuario se combinan distintas técnicas, relacionadas y no relacionadas con el usuario. Ejemplo de ello es el análisis de mercado sobre luminarias. A continuación, se describen las herramientas empleadas relacionadas con el usuario: seguimientos, entrevistas cortas contextuales, personas, y Cultural Probes.

Seguimientos

Esta es la primera herramienta empleada para tomar un primer contacto con el usuario y con el producto en cuestión. Consiste en involucrar al investigador siguiendo de cerca al individuo durante un periodo de tiempo predefinido (Milton y Rodgers, Looking, 2013).

Uno de los principales beneficios de observar a la gente en su entorno natural en vez de en un set más formal de investigación es que permite experimentar de primera mano y comprender las complejidades de las personas y su cultura. Así, se puede sumergir en la vida de los demás y presenciar sus patrones de comportamiento en contextos reales; es decir, estudiar lo que la gente hace en vez de lo que la gente dice, ofreciendo una perspectiva más realista (Milton y Rodgers, Looking, 2013). Para resumir las posibilidades de este método, se presenta la cita de Khoi Vinh, diseñador principal de Adobe, en sus reflexiones sobre el diseño de producto en 2014: “Pedirle a los usuarios que adopten nuevos comportamientos o que cambien los ya existentes es muy difícil”.

Muestra una serie de ventajas como son la: recolección en tiempo real de datos e información detallada sobre el comportamiento. Se centra en el usuario y genera una mayor empatía que otros métodos. Sin embargo, entre los inconvenientes están el alto consumo de tiempo y el análisis complejo de los datos recolectados (Think Design, s.f.).

Entrevistas cortas contextuales

Una vez finalizados los seguimientos, se optó por realizar unas entrevistas cortas contextuales a los mismos participantes de los seguimientos. Se busca comparar lo que hacen con lo que dicen que hacen, tratando de comprender más lo observado anteriormente para obtener una imagen completa del entorno y contexto del usuario.

Las entrevistas son una técnica cualitativa bastante común. Sin embargo, en este trabajo se aplica de una forma diferente: cortas y contextuales. Se caracterizan por llevarse a cabo en el momento en que el usuario está usando el producto, que junto al usuario, centran la investigación. Permiten comparar en tiempo real lo que dicen con lo que hacen. En cuanto a la estructura, siguen un guion más corto y abierto, donde hay que hablar menos y escuchar más para entender lo que dicen, sin centrarse en conseguir respuestas exactas.

El guion de preguntas de las entrevistas se puede encontrar en el Anexo. Este permite conocer los diferentes temas abordados para contextualizar los resultados posteriormente desarrollados.

Personas

Se trata de personajes ficticios basados en observaciones de la vida real de los usuarios con necesidades y objetivos específicos. Estas personas se crean para representar grupos de usuarios dentro del perfil demográfico con el que se trabaja que usan un mismo producto, servicio, marca, etc. (Milton y Rodgers, Personas, 2013).

Esta técnica se puede utilizar de distintas formas. Como material para provocar y exponer opiniones en sesiones de grupo (Ilstedt, Eriksson y Hesselgren, 2017) o, como se pretende en este trabajo, para comunicar los hallazgos de la investigación y facilitar su interpretación a la audiencia (Milton y Rodgers, Case Study -MJV Tecnologia e Inovaçao: SMS Coach, 2013 ; Wever, van Kuijk y Boks, 2008).

Los arquetipos se crearon para expresar los resultados de la investigación de una forma que fuera útil para los pasos posteriores a la investigación; es decir, guiar el diseño a través de unas personas ficticias, pero basadas en aspectos reales. Además, permite ver toda esa información de tipo cualitativa de forma visual, atractiva y resumida. Ayuda a: priorizar la audiencia y los requisitos de diseño y personificar las necesidades y los potenciales de diseño.

Es importante construir el set de personas en torno a los datos e información de la investigación y no en base a las suposiciones y estereotipos que uno tenga. Si no, en vez de representar a un grupo de la audiencia, será un arquetipo totalmente ficticio que probablemente no se ajuste a la realidad, siendo el resultado final incoherente con el resto de la investigación.

Entre los beneficios que ofrece la técnica, los más importantes son (Miaskiewicz y Kozar, 2011):

- Permite centrar la audiencia: se centra el desarrollo de producto en el usuario y sus necesidades.

- Prioriza los requisitos del producto: ayuda a determinar si los principales problemas se están resolviendo.

- Prioriza la audiencia.

- Cuestiona las suposiciones previas: desafía los estereotipos que uno tiene sobre los usuarios.

Por todo esto, permiten mejorar la comunicación con el equipo de diseño para que este pueda centrarse en el usuario, ayudándole a entenderlo mejor y construir alrededor de él (Milton y Rodgers, Personas, 2013).

Cultural Probes

Esta herramienta fue desarrollada en 1999 por Bill Gaver, actual co-director del Interaction Research Studio y profesor del Departamento de Diseño, ambos en la Universidad de Londres en un proyecto cuyo objetivo era involucrar a las personas de la tercera edad en sus comunidades y obtener una nueva perspectiva (Gaver; Dunne y Pacenti, 1999).

Consiste en, a través de un kit diseñado cuidadosamente y proporcionado a la audiencia con la que se esté trabajando, provocar, exponer y capturar respuestas inspiradoras que describan las relaciones del individuo con productos, espacios, servicios, etc. (Milton y Rodgers, Learning, 2013).

El kit está formado por diferentes artículos que permitan reunir una gran variedad de información de forma creativa. Por ejemplo, una cámara desechable, un diario, mapas, postales, etc. Los objetos que componen los kits se caracterizan por (Mattelmäki, 2006):

1. Basarse en la autodocumentación del usuario. El participante documenta el material que se le ha pedido para poder utilizarlo posteriormente en el proceso de diseño centrado en el usuario.

2. Mirar hacia el contexto y las percepciones personales. Permite introducir la perspectiva del usuario para enriquecer el proceso de diseño.

3. Explorar nuevas oportunidades de Diseño en vez de resolver problemas ya conocidos. Esto se ve favorecido por lo abierto que pueden llegar a estar las tareas propuestas para obtener un resultado inesperado o sorprendente.

Además, inspirándose en las Cultural Probes, muchos diseñadores e investigadores han seguido una interpretación en sus propios proyectos con diferentes motivaciones y enfoques. En definitiva, es una técnica que puede ser moldeada y diseñada según lo que se busque obtener de su aplicación, pues proporciona (Mattelmäki, 2006):

1. Inspiración: enriquece y apoya la inspiración del equipo de diseño.

2. Información: sobre los usuarios.

3. Participación: los usuarios finales del producto deben intervenir en la fase de ideación.

4. Diálogo: se crea un canal de comunicación entre usuarios y diseñadores.

Se decidió aplicar las Cultural Probes en el trabajo de la luminaria para obtener nuevas ideas o puntos de vista para la fase de ideación dentro del contexto del ocio y la relajación. Esta nueva información más personal sobre los usuarios complementa los hallazgos de la investigación. En definitiva, el fin de la investigación es diseñar una luminaria acorde con las necesidades del usuario objeto.

Resultados

Este apartado recoge los resultados de las diferentes etapas del proceso de diseño: investigación, ideación y desarrollo del diseño final. Cada una de ellas es consecuencia de los hallazgos de la etapa anterior.

Fase de Investigación

Seguimientos

Los seguimientos se realizaron a cinco personas dentro de la audiencia establecida de forma intensiva, con ciclos de observación de 5 horas ininterrumpidas a partir de las 19 horas de la tarde en adelante, tomando nota de los comportamientos y hábitos desde que comienza a anochecer hasta que deciden acostarse.

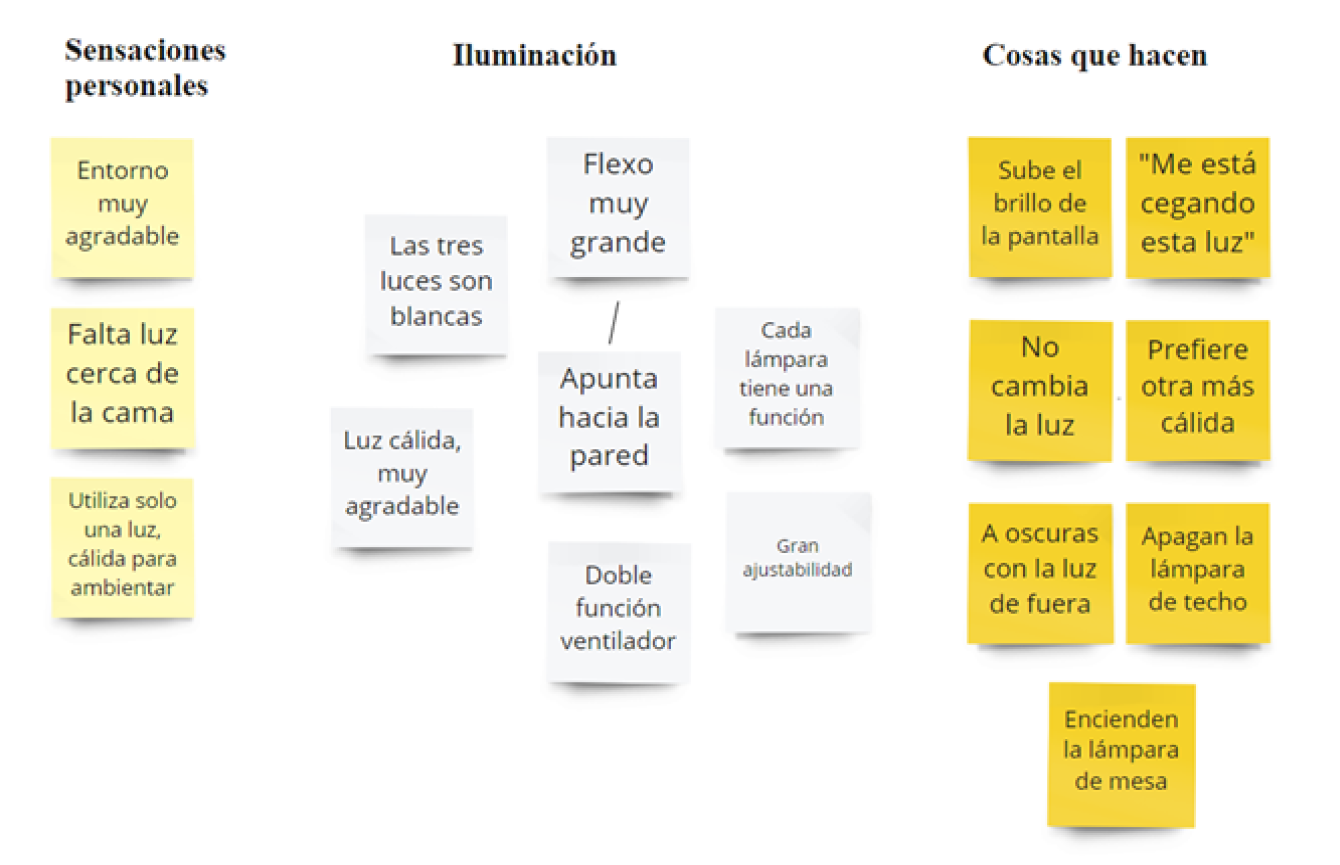

Durante el periodo de seguimientos se observaron diferentes conductas y hábitos: desde momentos de ocio, hasta de estudio y relajación que permitieron recolectar una información cualitativa que queda resumida en la Figura 2. Esta queda agrupada en tres columnas: 1. Impresiones del observador sobre el entorno que rodea al observado; 2. Características de la iluminación que emplean los observados; 3. Actividades que realizan y hábitos de luz que tienen los observados.

Figura 2. Clasificación de las anotaciones.

Las sensaciones personales tienen que ver tanto con lo que hacen, como con la luz y el lenguaje personal; es decir, con el entorno que les rodea. Hay que destacar la sensación de que siempre falta una lámpara de mesa para momentos distendidos y de relajación. Normalmente este problema queda resuelto o bien con el típico flexo de estudio, a pesar de que no proporciona una luz adecuada (por intensidad o por tono); o bien con la lámpara de techo, que ofrece demasiada luz para instantes de desconexión.

El siguiente bloque de anotaciones trata las características de los objetos de iluminación: su luz, sus funcionalidades y la forma de usarlos. Todos los participantes contaban con lámparas de mesa. Unas más grandes y otras más pequeñas y con diferentes grados de ajuste. Muchas veces dicho ajuste se utilizaba precisamente para lograr el grado de intensidad deseada, pero no para trabajar, sino para relajarse y generar una iluminación ambiente apuntando hacia la pared, mesa, etc.

Finalmente, la tercera columna se centra en las observaciones sobre los hábitos de luz establecidos. Los participantes solían intercambiar luces según lo que estuvieran haciendo (cocinar, cenar, ver la tele...) A pesar de tener infinidad de posibilidades, algunos emitían quejas sobre algunas de ellas debido a la falta de una luz adecuada.

En definitiva, se detecta una necesidad en la iluminación para momentos de relajación y desconexión, aunque siempre hay formas de sustituirlo a través de la iluminación que ya se tiene de diversas formas: con el flexo, la lámpara del techo, encendiendo una que esté lejos, apuntando hacia otro lado, etc.

Entrevistas Cortas Contextuales

Para contrastar la información cualitativa recolectada anteriormente, se realizaron las entrevistas a las mismas cinco personas siguiendo el guion antes presentado con un claro enfoque al tiempo libre para profundizar en ese aspecto de su día a día. Tras reunir y analizar toda la información, a continuación, se describen los hallazgos más relevantes. Aunque se extrajeron diversas conclusiones, las más relevantes tenían que ver con los hábitos y rutinas del usuario.

Uno de los hábitos más repetidos fue el tender a estar a oscuras. Esto se entiende como la preferencia por utilizar luces tenues donde la oscuridad prevalece sobre la iluminación. Suele estar relacionado con los momentos de relajación y desconexión. La respuesta “la comodidad de una luz tiene que ver, en gran parte, con la oscuridad que deja” es un reflejo de esta primera conclusión. También hay que destacar la falta de recursos, ya sea en forma de lámparas o de interruptores y enchufes. Como consecuencia, emplean lámparas para funciones que no son para las que fueron diseñadas, como un flexo apuntando a la pared en vez de al puesto de trabajo.

Al preguntar a los usuarios sobre posibles desperfectos en sus lámparas, estos afirman tener problemas con algunas piezas más pequeñas que se encuentran a simple vista, y pueden sugerir un aspecto más compacto y robusto. Mientras que unos señalaban que no han intentado arreglarlo y que conviven con ello, otros sí que dicen tener que revisarlo de vez en cuando para poner las piezas en su sitio. Por último, cabe destacar la dificultad que a veces encontraban para ajustar sus luminarias o la luz; es decir, tener esta funcionalidad no siempre resulta cómodo.

Tras cada entrevista, se analizaron las respuestas, con el fin de mejorar iterativamente la forma de abordar las preguntas y temas. Algunas preguntas no ofrecieron el contenido que se esperaba por estar mal planteadas pudiendo crear confusión. Completadas las entrevistas y recolectada y analizada la información cualitativa, se decidió pasar a la siguiente fase de la investigación para dar forma a los hallazgos.

Hallazgos

Un hallazgo se puede definir como un nuevo punto de vista que lleve a reexaminar convenciones consecuencia de una observación del comportamiento humano; es decir, un descubrimiento sobre las motivaciones y necesidades que impulsan las acciones de las personas (Dalto, 2016). Permiten identificar la información relevante para generar valor (Design Thinking en Español). Este apartado recoge los hallazgos finales más importantes extraídos, fruto de las técnicas empleadas para acercarse y conocer al usuario:

1. Sistemas de iluminación deficientes para sus hábitos. Ha quedado demostrado tanto en los seguimientos con sus actos como en las entrevistas con sus palabras, que los jóvenes no disponen de una correcta iluminación para sus actividades nocturnas. Estas tienen que ver en su mayoría con momentos de relación, ocio y desconexión. En muchos casos, se utilizan lámparas para tareas en las que, si pudieran, utilizarían otras fuentes de luz.

2. Una doble función es atractiva de ver, pero no de usar. Si bien puede resultar seductora una doble función, independientemente del objeto, en un catálogo, video o en persona mismo; lo cierto es que, a la hora de usarlo, muchas veces no se aprovecha.

3. Es tan importante la luz que da, como la oscuridad que deja. Cuando se habla de una luz, se comenta su intensidad. En algunos casos de la investigación definen alguna de las luces que usan como muy fuertes, que pueden ver hasta con los ojos cerrados. Esta nueva interpretación consiste en darle la vuelta a lo que es considerar una luz. Ese grado de oscuridad que deja una luz tenue es la que hace que sea agradable de usar, creando ambientes apacibles.

4. Hay lámparas cuya funcionalidad no converge con la usabilidad. Se ha visto en la investigación casos de lámparas con un alto grado de ajuste; aunque con defectos a la hora de usar. En una de ellas, las uniones estaban flojas y era complicado fijarla. Otra tenía muchas formas de ajustar la posición, tantas, que no era cómodo e intuitivo de hacer.

5. Una lámpara no es solo la luz que da. El aspecto físico de una lámpara también es importante. Aunque no todo el mundo valore por igual la estética, siempre se tiene en cuenta a la hora de comprar. A pesar de ser algo subjetivo, el cuidado de la estética es algo que se puede percibir y reflejar, sobre todo, a través del detalle y el cuidado de todos los aspectos que componen el producto, en este caso, una lámpara.

6. Son productos con un largo periodo de vida. Una lámpara es un producto duradero. No suele cambiarse a menudo. Reflejo de ello son las lámparas infantiles o los flexos para estudiantes. Para transmitirlo en un producto, se le puede dotar de un aspecto atemporal, con un estilo marcado, sin encasillarlo en una tendencia decorativa. Del mismo modo, un diseño robusto puede estar relacionado no solo con la apariencia, sino también con la durabilidad.

7. Se está más cómodo y relajado con una luz cálida. Por muy obvio que pueda parecer, es importante poder demostrarlo directamente a partir de las propias palabras y experiencias del usuario. Este tipo de luz favorece los entornos distendidos y agradables.

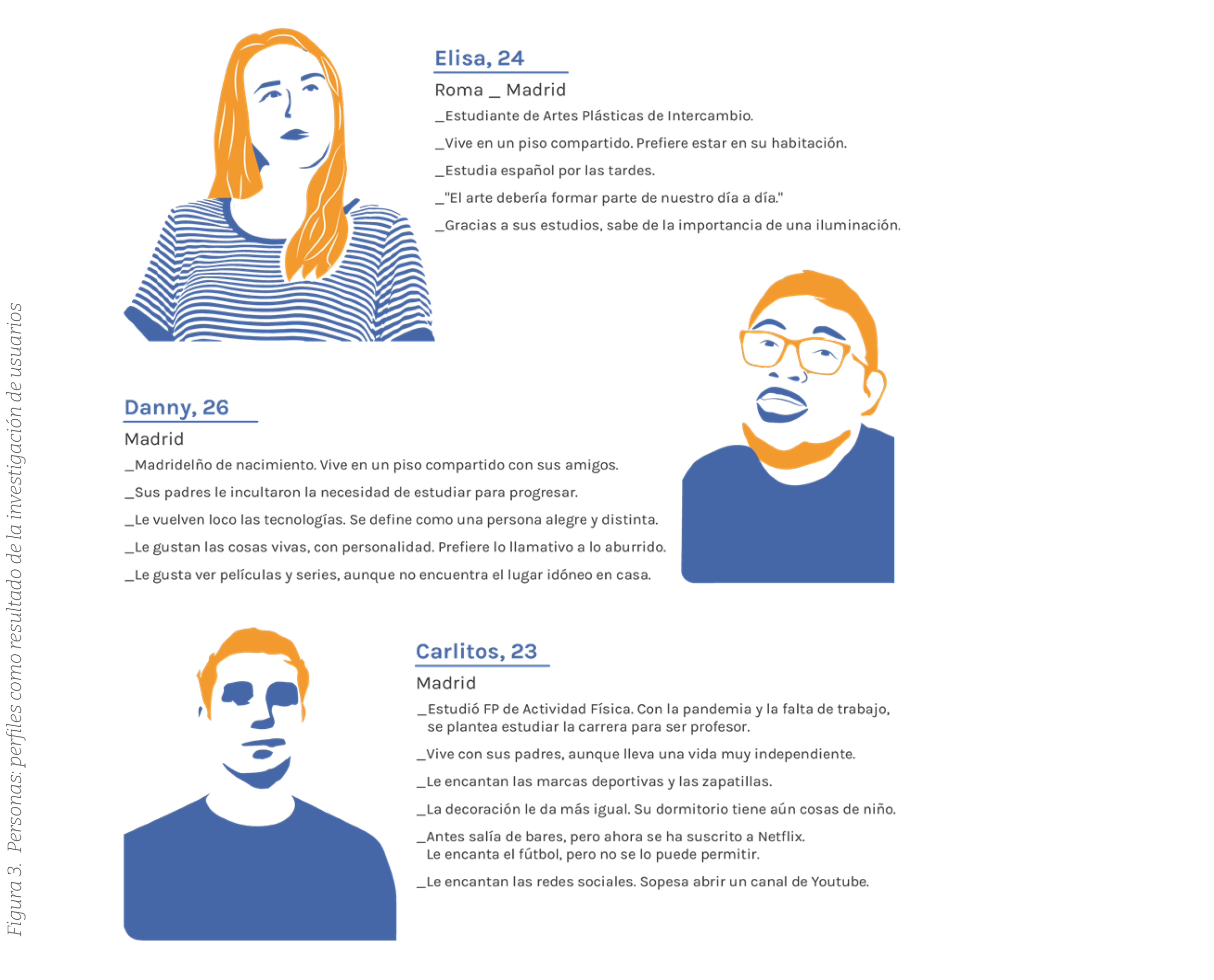

Personas

Las tres personas creadas con el fin de poner cara al usuario en la fase de diseño e ideación se muestran en la Figura 3. Estos perfiles reflejan sutilmente en su propia construcción los hallazgos antes descritos.

Reto de diseño

Mediante un objetivo como es el reto de diseño se pretende recalcar las necesidades del usuario que se han descubierto durante la investigación. Dicho reto es: Potenciar los momentos de relajación en el tiempo libre.

Durante la investigación se conocieron los hábitos, gustos estéticos, las cosas que les gusta hacer, etc. Observando las rutinas, el estudio y el trabajo prácticamente absorben el día a día, incluida parte de la tarde, quedando parte de esta y de la noche relativamente libres. Aquí es cuando la iluminación que se tiene comienza a dar problemas: luz muy fuerte, muy focalizada, demasiado blanca, etc. Estos problemas aumentan cuanto mayor es el tiempo que se les dedica a estas actividades de ocio y tiempo libre, pudiendo llegar a generar rechazo e incomodidad.

Si bien es cierto que uno tiende a adaptar los medios que tiene a lo que quiere hacer, mucho más interesante y atractivo resulta tener los medios adecuados para ello. En eso consiste el reto, una luminaria que potencie las actividades preferidas para relajarse y entretenerse. Es invitar a las personas a dedicarse más tiempo a si mismas y darle más importancia a sus costumbres y gustos ofreciendo los medios adecuados. En este caso, sistemas de iluminación que favorezcan el disfrute de los momentos de ocio y tiempo libre.

Fase de Ideación

Cultural Probes

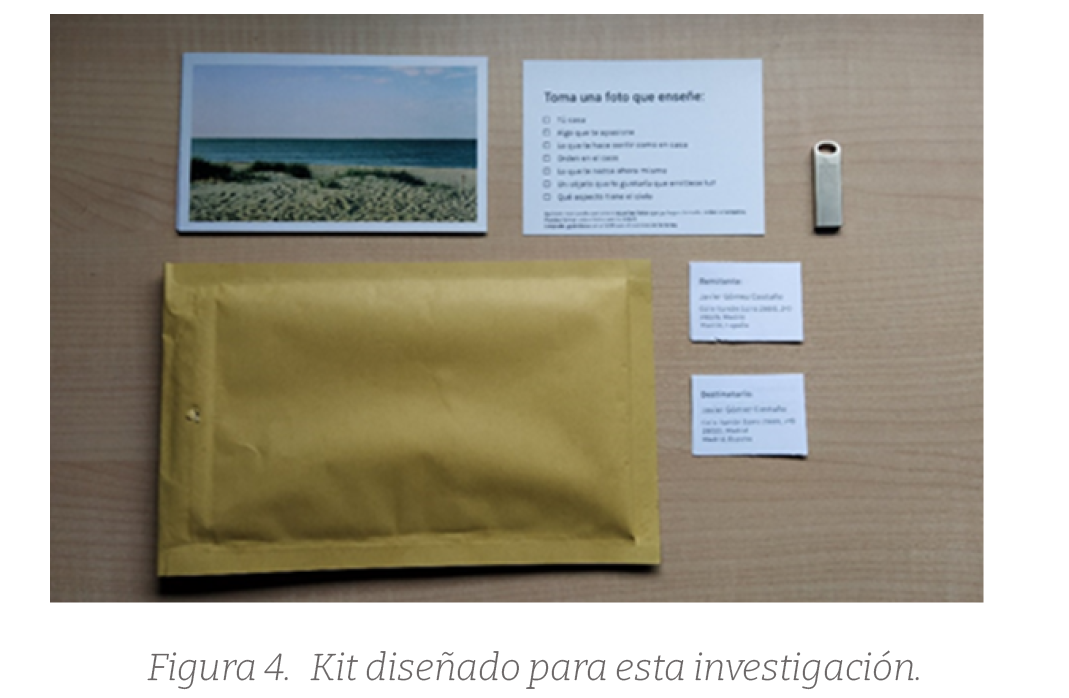

Tras terminar la fase de investigación, y con el carácter inspirador e íntimo mencionado anteriormente, se preparó el material para llevar a cabo la técnica Cultural Probes. El kit fue distribuido por correo a cuatro personas diferentes de las anteriores y dentro de la audiencia definida para este trabajo. Se diseñó para que todas las tareas fueran completadas en un par de semanas, aunque se dio libertad a cada participante para realizarlas en el orden y el tiempo que consideraran. Aludiendo al carácter inspirador y temporal de esta técnica, el kit se construyó con postales y fotodocumentación. A continuación, se describe el contenido (Figura 4):

- Un sobre.

- Una tarjeta explicativa de las tareas.

- Siete postales.

- Una tarjeta con los motivos que deben ser fotografiados.

- Un USB para guardar las imágenes digitales.

- Pegatinas con direcciones de destinatario y remitente para enviar las respuestas.

- Un sello para el envío de vuelta del sobre.

Tanto las postales, como las instrucciones para la fotodocumentación presentaban una dificultad variada, habiendo tareas más fáciles y tangibles y otras de mayor reflexión interna. Las postales tenían una imagen principal relacionada con el dorso, donde había una pregunta que debía ser respondida a continuación. Las tareas y las preguntas se muestran en la Tabla 1:

Tras recibir las respuestas, se procedió a su análisis. Una de las principales conclusiones que se pudo extraer fue la importancia de la naturaleza, pues fue relacionada con la calma, la oscuridad, el lugar para ver el atardecer, etc. De hecho, la playa fue la respuesta más repetida al preguntar por un lugar favorito para estar. De este modo, la naturaleza será una fuente de inspiración más adelante ya que fueron los propios usuarios los que destacaron su necesidad de tenerla más presente.

También se preguntó por el tipo de actividades que se hacían cuando querían desconectar. De esta forma, se puede entender qué rutinas y actividades son las que a los usuarios les gusta hacer acorde al reto de diseño planteado. Los hábitos para desconectar detectados fueron muy variados: dibujar, estar sentado o tumbado en la cama, comer, tocar el piano, ver una serie... Aunque algunas requieren mayor intensidad de luz, son actividades que se caracterizan por necesitar, más bien, una luz tenue y cálida, creando entornos acogedores.

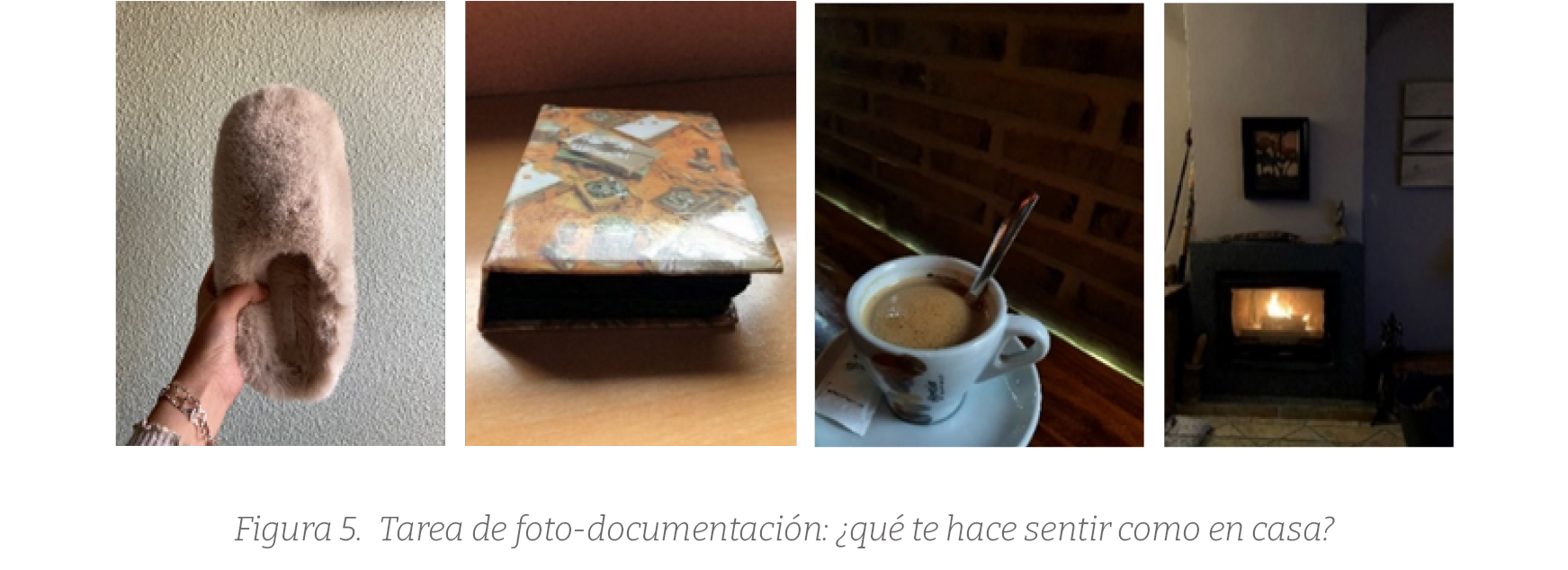

De las fotografías se puede destacar la tarea de reflejar aquello que les hiciera sentirse como en casa. En la Figura 5 se puede ver que cada uno escogió un objeto diferente.

El diseño final puede nutrirse de estas ideas para generar la misma sensación, como la forma acogedora de la zapatilla o el calor que desprenden un café y una chimenea.Estas tareas fueron las más relevantes para luego elaborar nuevas ideas y conceptos con los que desarrollar la lámpara basados en la naturaleza como inspiración, en las aficiones para su adaptación y basados en objetos cotidianos para emular ese lenguaje formal y emocional para integrarse con ellos. El resto de las respuestas contribuyeron también a conocer los puntos de vista de los participantes, la forma de pensar y a entender mejor sus contextos.

La acogida de esta técnica entre los cuatro participantes fue positiva, pues mostraron su interés por el proyecto y por los siguientes pasos que tomara. En otras condiciones con mayor disponibilidad de tiempo, se podrían haber añadido más elementos al kit para enriquecer el proceso. Un aspecto importante para el desarrollo Cultural Probes fue seleccionar perfiles dentro de la audiencia con unas características como: personalidad reflexiva, con interés por el arte y gente curiosa por conocerme a sí mismos y explorar nuevos productos e interacciones, etc.

Exploración de ideas

Sintetizadas las fases de investigación y la técnica anterior, se exploraron las ideas surgidas. La principal línea de trabajo se centró en la lámpara portátil.

Si bien es cierto que en las entrevistas no todo el mundo señaló esta opción como preferente, es una característica que hace que la lámpara sea adaptable al uso, permitiendo colocarla allá donde se desee.

En la Figura 6 se aprecia otra línea de trabajo que trata de acercar la naturaleza y la playa, mencionadas en las respuestas de las postales. Se busca transportar sensorialmente al usuario a través de esos efectos de luces y sombras tan característicos del agua en la orilla del mar a través de superficies de vidrio. Se consigue llevar esa sensación de calma de la playa a casa, donde se quiere potenciar los momentos de desconexión.

Como se puede ver en la figura, los reflejos aparecen cuando sus paredes de vidrio son atravesadas por una luz concentrada y potente. Este efecto, en términos físicos y de óptica, se denomina caústica y son el resultado de la refracción y reflexión de la luz sobre una superficie curva.

La regulación de la intensidad es un tema que surgió en las observaciones. A veces, la luz era muy intensa para el uso que se deseaba; y al revés. Poder regular la intensidad acorde a la actividad es una tecnología hoy en día disponible y que puede potenciar esas actividades de desconexión con una iluminación adecuada por la cual apetezca dedicarle tiempo a ello.

La luz que dé la luminaria será para acentuar y ambientar una estancia para crear entornos acogedores y recogidos donde la luz es tan importante como la oscuridad que deja, invitando a un estado de ánimo más reflexivo y de desconexión.

Los conceptos se fueron explorando y desarrollando, haciendo uso de técnicas de dibujo. Se definieron y desecharon ideas de diseño hasta dar con la que mejor incorporaba estas premisas.

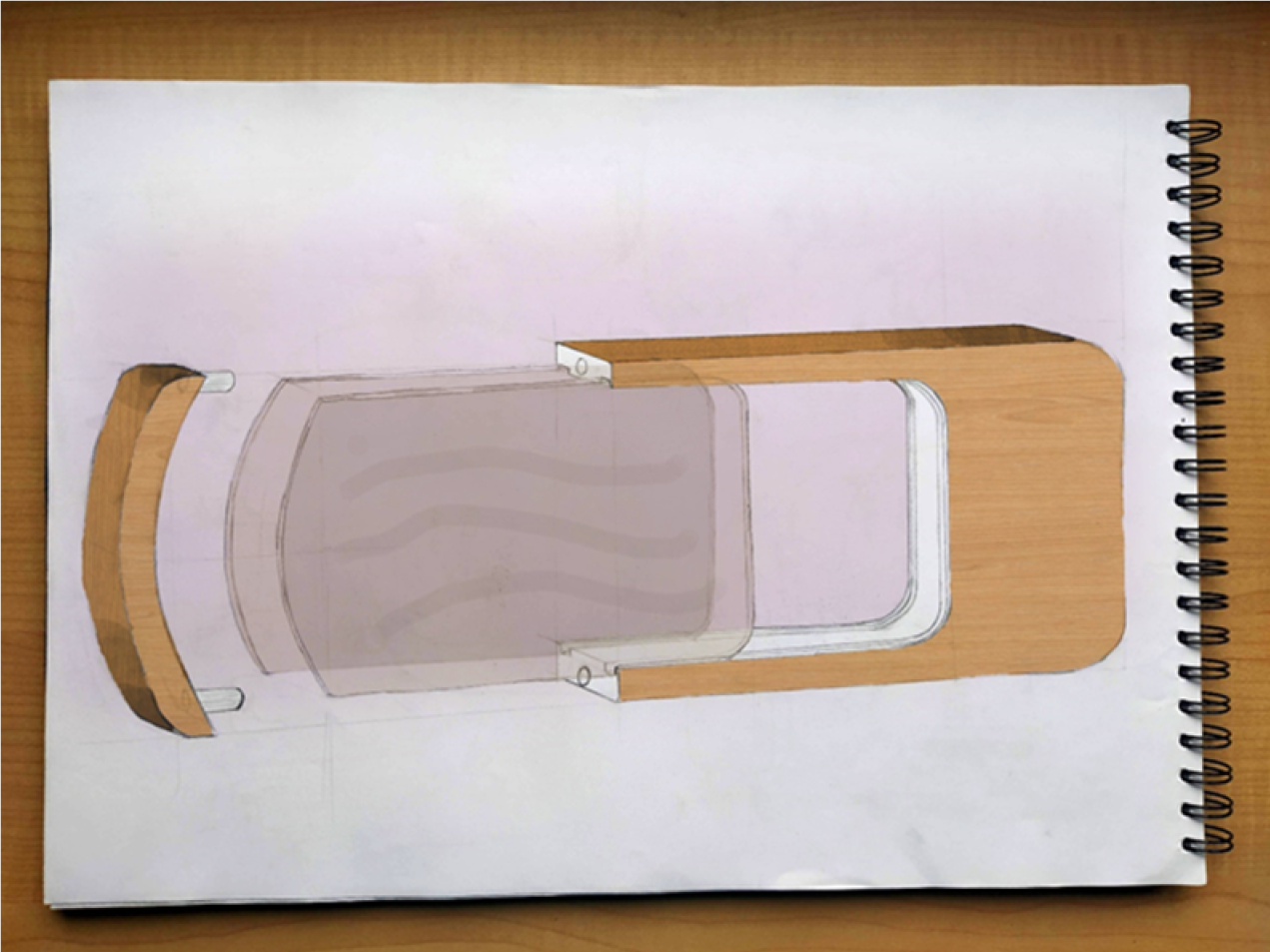

El boceto de la Figura 7 muestra la propuesta de diseño de la que posteriormente resultaría en el diseño final de la luminaria: lámpara portátil, regulable y que crea efectos de luz tanto cuando está encendida como cuando atraviesa la luz natural las paredes de vidrio.

Figura 7. Ensamblaje de la propuesta de diseño.

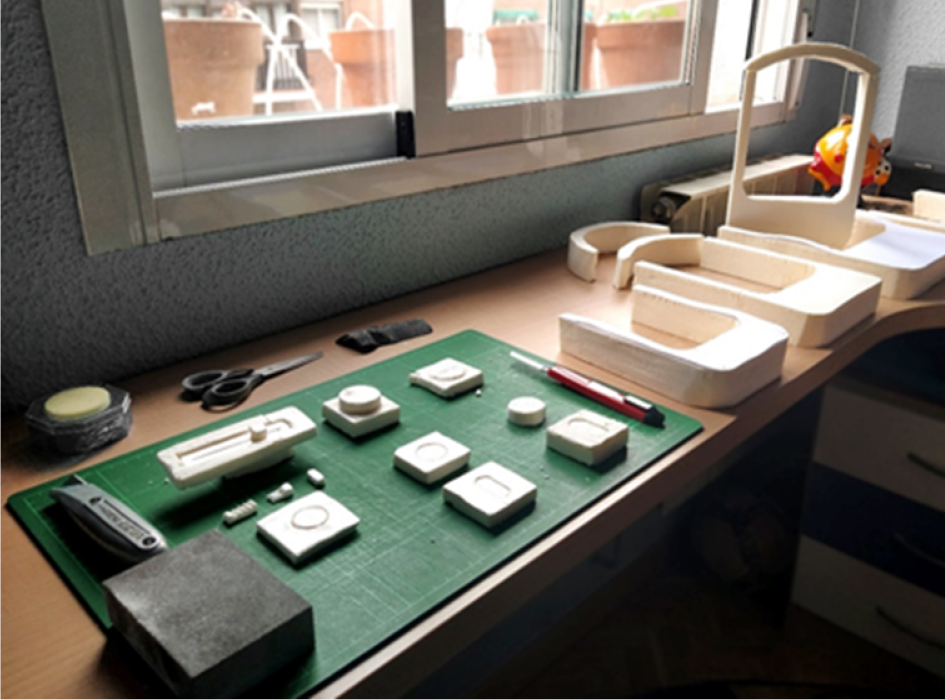

Para completar el proceso de definición, se construyó un modelo con el fin de determinar las dimensiones y posiciones de distintos elementos para optimizar la interacción con el producto. La figura 8 recoge el trabajo creado durante este proceso.

Figura 8. Proceso iterativo de construcción del modelo.

El prototipado rápido permite experimentar con objetos físicos de cualquier complejidad con rapidez (Chee Kai y Kah Fai, 2000); observando con más claridad diversas ideas. Además, ayuda a identificar problemas de un producto que pudieran pasar desapercibidos si se trabajara únicamente con herramientas digitales donde hay otros factores más difíciles de interpretar. Se logra un mayor entendimiento de las formas y los volúmenes del diseño final. Como se muestra en la Figura 8, su naturaleza lleva implícita la exploración de ideas, añadiendo y quitando elementos mientras se prueban diferentes combinaciones. Para ello se emplean materiales económicos como la espuma de poliestireno antes de acudir a los softwares especializados para el modelado en 3D (Milton y Rodgers, Quick-and-dirty prototypes, 2013).

Fase de Desarrollo

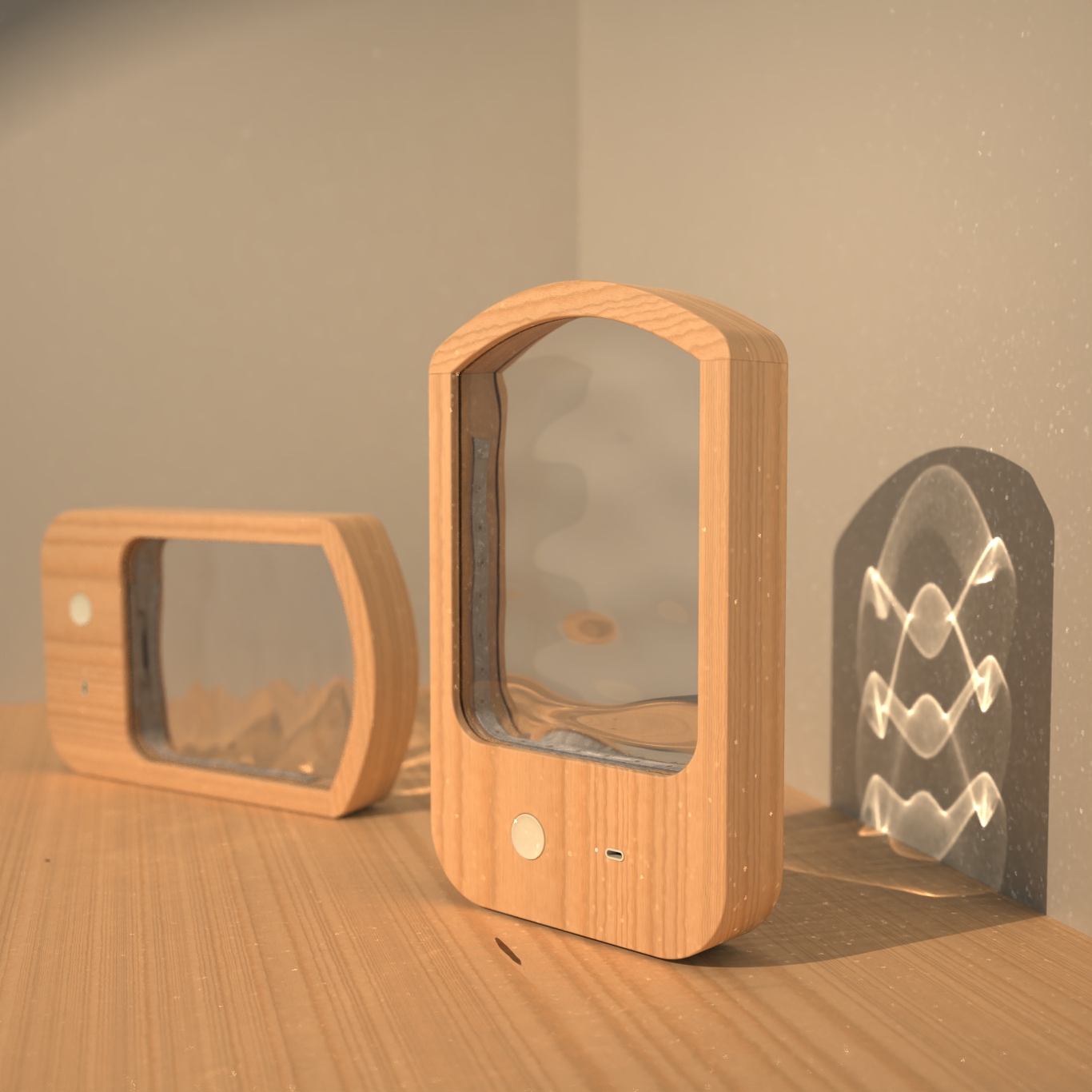

La luminaria diseñada se muestra en la Figura 9. Tiene como objetivo principal potenciar los momentos de relajación en el tiempo libre. Se trata de una lámpara de mesa portátil con intensidad regulable. Además, presenta dos posiciones: vertical y horizontal, para ser colocada según se desee.

Figura 9. Efectos de luz al ser atravesada por la luz.

Su característica principal es la creación de efectos de luz mediante reflejos y sombras creados por las paredes de vidrio que simulan los efectos tan característicos del agua cuando le atraviesan los rayos de luz del sol y que están asociados a momentos de calma y relajación como un atardecer de verano en la playa o en el río.

Como se puede ver en la figura, los reflejos aparecen cuando sus pantallas de vidrio son atravesadas por una luz concentrada y potente como consecuencia del efecto físico de caústica.

La intensidad de la luz que emiten puede regularse mediante el pulsador táctil con cuatro niveles (0% - 25% - 50% - 100%).

La Figura 10 muestra los diferentes niveles de intensidad. La luminaria presenta una entrada de carga de tipo C y un punto luminoso a su izquierda que indica, durante el proceso de carga, si la batería está cargada completamente (luz verde) o no (luz roja).

Así, queda presentada brevemente la luminaria resultante de un proceso de investigación centrado en el usuario y de diseño industrial y desarrollo de producto. Una fase posterior será el prototipado físico y funcional que permita testar y verificar con el usuario el resultado como una última etapa del proceso de Diseño Centrado en el Usuario que permita descubrir si satisface las necesidades descubiertas e identificar posibles cambios para refinar el diseño final.

Conclusiones

El Diseño Centrado en el Usuario es un enfoque cada vez más empleado tanto en el diseño industrial como en otros campos del diseño, (servicios, producto digital, etc.). Mediante este proyecto de investigación y diseño se ha querido explorar las diferentes etapas que se deben seguir para diseñar nuevos productos: conocer el contexto del usuario, una ideación creativa, bocetado y la definición de propuesta, entre otras.

Sin embargo, donde más hincapié se ha realizado es en la investigación del usuario para crear, en este caso, una luminaria que responda a sus necesidades e inquietudes. Se emplearon técnicas creativas, entendiendo por creativas aquellas diseñadas especialmente para obtener una información concreta. Ejemplo de ello son los seguimientos a usuarios para comprender hábitos y rutinas relacionados con la luz.

Cada técnica empleada de la investigación tiene su justificación en los resultados de la herramienta previa, remarcando el carácter iterativo del Diseño Centrado en el Usuario. Por ejemplo, las entrevistas se realizaron después de los seguimientos para poder resolver ciertas dudas anotadas en los periodos de observación y para comprobar y comparar lo que el usuario dice y hace.

Esta combinación de seguimientos – entrevistas contextuales ha resultado ser efectiva para obtener una imagen completa del contexto del usuario. Mientras que las observaciones permiten obtener una imagen directa y sin la deformación de la perspectiva usuario, las entrevistas dan la oportunidad de entender cómo el usuario percibe su realidad y entorno.

Dado que los seguimientos y las entrevistas tenían como participantes a las mismas personas, pudiese haber sido más fructífero para la investigación haber personalizado más el guion de cada entrevista para así poder aprender y extraer los distintos matices de cada usuario. Sin embargo, las observaciones de los seguimientos abrieron la línea centrada en buscar nuevas formas de adaptar la iluminación a las tan diversas actividades de ocio y desconexión del día a día. Permitieron estudiar y comprender las interacciones actuales con la luz para poder diseñar la luminaria. El análisis del uso que los usuarios le daban a sus lámparas estáticas y de intensidad lumínica excesiva o insuficiente en incómodas posiciones y ubicaciones guio el trabajo hacia la lámpara portátil de intensidad regulable, permitiendo que el usuario en todo momento coloque la luminaria donde desee con la intensidad que más le convenga en cada momento. Es decir, los seguimientos permiten estudiar cómo los usuarios utilizan los productos, para así poder diseñar nuevas dinámicas de uso, funciones y tecnologías que se adapten a las necesidades y hábitos de las personas.

Si bien los arquetipos ficticios no tienen una relación directa con el diseño final, sí han sido de gran utilidad durante el proceso de diseño para poder tener presente al usuario. Esto ha sido gracias a que en su definición, los perfiles reflejan de manera más superficial los hallazgos de la fase de investigación. Así, resulta más sencillo asociar los problemas y las necesidades con el usuario final, dándole un contexto construido a partir de las observaciones y entrevistas reales realizadas anteriormente.

La técnica que se podría considerar más vanguardista y conectada con el usuario es Cultural Probes. Permite crear un canal de comunicación fuera de un entorno que puede condicionar al usuario; es decir, en vez de sentirse estudiado, mediante esta herramienta se logra una aproximación más lúdica y personal. Es el usuario el que decide qué información da al investigador. Se encuentran hallazgos menos superficiales y que tienen que ver con los puntos de vista y reflexiones de los participantes sobre el tema principal del proyecto u otros de su contexto.

Gracias a esta herramienta, se pudo identificar otras necesidades y deseos de los usuarios, como un mayor contacto con la naturaleza. Las respuestas obtenidas influenciaron el diseño final, ya que incluían información sobre en qué entornos y contextos afloraba esa sensación de tranquilidad y sosiego; como, por ejemplo, el atardecer en la orilla del mar, con el oleaje. Este sería clave después, ya que los efectos ópticos de la lámpara tratan de emular este momento para transportar sensorialmente al usuario.

Hay que destacar un último detalle de la investigación centrada en el usuario. Las personas muestran interés por participar, pues realmente sienten que los nuevos productos que emerjan de la investigación están diseñados para responder a sus necesidades y deseos. Por tanto, si se emplean técnicas que favorezcan su participación que sean explicadas de forma precisa, las personas se encuentran predispuestas a involucrarse, incluso más de lo que el investigador espera. Como resultado, se obtienen unos hallazgos muy útiles e interesantes para el equipo de diseño, que debe plasmarlos en los productos.

El proyecto presentado sigue esta línea; es decir, los hallazgos de la investigación sustentan el diseño final, pues el proceso de diseño y desarrollo se nutre de las personas creadas y los descubrimientos presentados. Después de la investigación y la ideación viene el proceso de desarrollo de la propuesta. Además de lo que se presenta en este artículo, se profundiza en otros aspectos más técnicos propios del Diseño Industrial y la Ingeniería, como las conexiones de la luminaria o el cumplimiento de la normativa asociada.

Aunque es una metodología que hoy en día está mejor implementada en el diseño de productos de carácter digital, su irrupción en el producto físico puede ser diferenciadora, e innovadora, justificando los diseños, generando una propuesta de valor y dándoles una personalidad enfocada al usuario y la experiencia de interacciones, donde el producto responde a las necesidades de la persona.

En definitiva, este proyecto trata de poner en valor la necesidad de una correcta fase de investigación siguiendo la metodología propia del Diseño Centrado en el Usuario con el fin de que los nuevos productos respondan a las necesidades de las personas, independientemente del campo del diseño que se aborde. Ello permitirá que los productos tengan una mejor acogida posteriormente en el mercado, así como un gran respaldo en forma de conocimiento del usuario y sus hábitos y necesidades que lo sustente. Se trata de una metodología abierta, que debe ser diseñada y adaptada a cada usuario y producto para poder extraer la información relevante.

El trabajo abordado en este artículo podría haberse complementado con una mayor involucración de usuarios o bien con el uso de otras técnicas que hubieran permitido observar cómo el usuario interactúa con los objetos de iluminación para así enriquecer más los hallazgos posteriores. Se abre así una línea investigación posterior que tiene que ver con el prototipado y la verificación del diseño aquí presentado para estudiar la aceptación del usuario y posibles mejores, sobre todo en dicho aspecto de las interacciones con el producto para ajustarlo más a las necesidades y los hábitos de las personas, fin último de esta metodología.