Framing user experiences through personal dilemmas

Framing and reframing problems is considered a foundational concept in design research and a key design skill in practice (e.g. Schön, 1983; Hekkert and Van Dijk, 2011; Dorst, 2015). Framing can briefly be defined as the creation of a new perspective on a design task or a novel standpoint from which a problem situation can be tackled (Dorst, 2015). Schön’s (1983) model of reflective practice forms a solid foundation for problem-framing in design. In one article, Schön (1984) explicates how conflicting frames manifest in design dialogues in which two fundamentally different design perspectives clash (open and flat vs. palace-like hierarchical building structures). This clash raises the question of ‘how to design a building that rejects hierarchy while still being easy-to-navigate?’ and demonstrates how conflicting frames might be creatively negotiated in design practices. Following Schön’s work, problem-framing continued to develop as a creative and situated design activity (e.g. Paton & Dorst, 2011; Pee, Dorst & van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2015; Vermaas, Dorst, & Thurgood, 2015) that is intertwined with the co-evolution model of design creativity (Dorst & Cross, 2001; Dorst, 2011; Crilly, 2021). More recently, framing practices have been linked to social design and innovation (Van der Bijl-Brouwer, 2019), and simultaneously, they attracted scholarly criticism for barely recognizing the political dimensions of how they organize social and moral experiences (e.g. Santamaria, Prendeville, & Syperek (2021).

Given its increasing theoretical and practical significance, developing methods to support and improve problem-framing in design seems essential. One method that promises a framing capacity in design is what I call Dilemma-Driven Design (DDD) (Ozkaramanli, 2017). Borrowing from Badke-Schaub, Daalhuizen and Roozenburg (2011, p.181), design methods can be defined as mental tools that “provide structure and support designers in dealing with complex and complicated problems in varying projects, contexts and environments”. DDD is an emerging method to design for experience that considers personal dilemmas as valuable starting points for understanding end-users and conceiving innovative design ideas. In what follows, I position DDD as an emerging method that can be used to frame human experiences through a specific lens: the lens of personal dilemmas. For this, I zoom into the ‘framework of dilemmas for designers’ as part of the larger DDD method and discuss the contribution of this tool to problem re-framing when designing for experience.

Finding dilemmas is finding frames

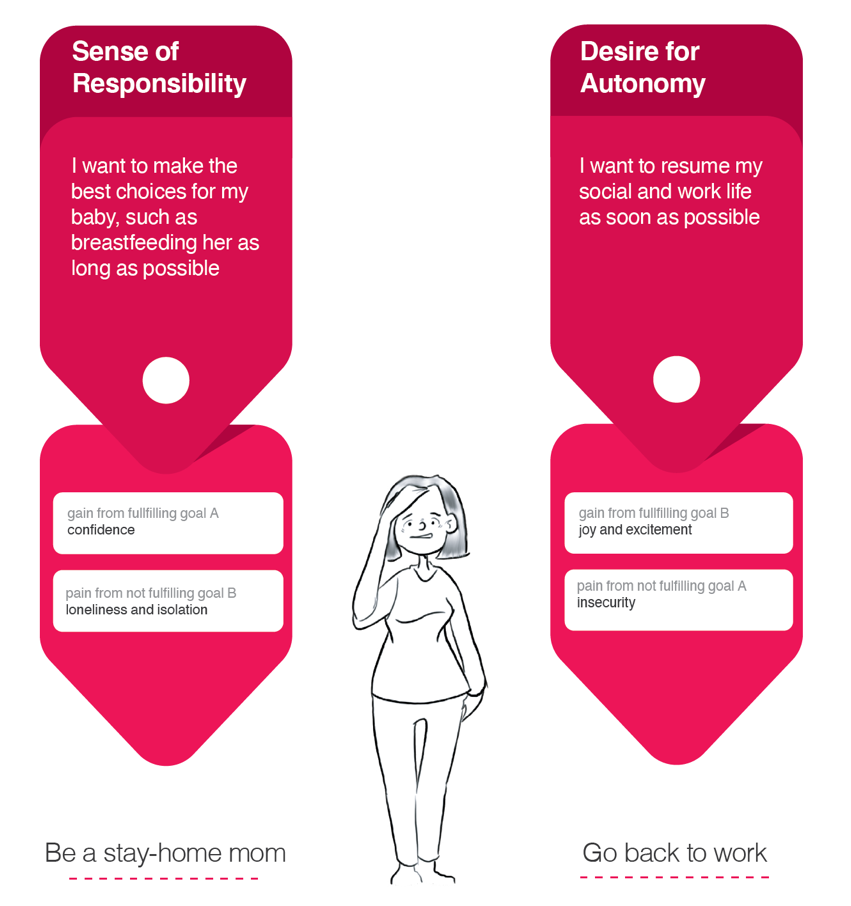

In the context of designing for experience, dilemmas can be defined as multi-faceted psychological phenomena that have behavioural, emotional, and motivational underpinnings (Ozkaramanli, 2017). Imagine, for example, that you are a new mother who wants to breastfeed her baby for as long as possible, but also wants to go back to work as soon as possible. At the behavioural level, a forced decision may be implied between two mutually exclusive choices: Do you extend your maternity leave or go back to work? At the emotional level, both choices may evoke mixed emotions: If you extend your leave, you may feel confident that you are doing the best for your child, but you may also feel isolated from social and work life. On the other hand, if you go back to work, you may experience joy and excitement, but you may also fear failing as a new mother. At the motivational level, these choices are underpinned by conflicting goals. In this hypothetical example, these goals are the sense of responsibility and the desire for autonomy, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates this hypothetical dilemma using the framework of dilemmas that is specifically developed for designers.

At first sight, the framework of dilemmas might seem like a humble illustration of a complex experience. Its real value unfolds when used as a canvas for reflecting on and discussing the deeply-held motivations and emotions that underlie human behaviour. Although the content of the framework may change based on the specific situation being analysed, its proposed three-part structure (i.e. goals, emotions, choices) remains intact. This makes it feasible to gather and compare different dilemmas that are relevant for a design project and to find new connections among them.

Designers who have worked with DDD often comment that the framework ‘brings order to chaos’ and ‘helps pinpoint meaningful and manageable design challenges’ as part of a larger project context. These comments point to the main contribution of this framework: It facilitates reflection, discussion and the creation of new perspectives when exploring design problems. In frame creation, Dorst (2015) refers to this process as broadening of the problem space instead of directly tackling the dilemma (cf. the ‘paradox’ in Dorst, 2015). The multi-faceted nature of dilemmas; therefore, helps understanding the “deeper issues and needs that are at play in the problem situation” (Dorst, 2015, p.26). In addition, gathering and comparing multiple dilemmas can lead to common themes across them, which can then be taken as a starting point for generating design ideas to tackle them.

Practical design tools, such as the framework of dilemmas, may come with risks if not implemented with care and intellectual curiosity. The risk here is to use this framework as a ‘mathematical formula’ to ‘solve’ design problems. In fact, the framework as depicted in Figure 1 does not disclose the rich context dilemmas are often situated in. It only outlines the three main components (i.e. goals, emotions, choices) that represent the essence of a dilemma, which are, on their own, not enough to convey the complexity of design situations. Therefore, it is best to complement the dilemma framework with short narratives (e.g. a scenario) which can restore the richness of the context in which dilemmas are situated. This will help increase the understanding of the problem context and facilitate communication within the design team as well as with other relevant stakeholders.

Choosing dilemmas is choosing frames

Depending on the size of a project, a design team often identifies multiple dilemmas that are relevant for a given design brief. To give an indication, in a large scale innovation project conducted over three weeks of ethnographic research, the design team identified nine dilemmas (Ozkaramanli et al., 2013). A six-month, master-level student design project may deal with four-to-six dilemmas. Dilemmas can be distilled through literature research into a certain domain (e.g. parenting). In addition, contextual research (e.g. interviewing, generative sessions) can be conducted to capture goals and dilemmas of a particular group (Ozkaramanli, 2017). Since dilemmas are complex mental phenomena, they can rarely be captured through direct observations. They sometimes come up in interview settings with end-users; and more often than not, they emerge in the form of conflicting themes when analysing qualitative data gathered during contextual user research (Ozkaramanli et al., 2013).

In DDD projects, every personal dilemma can be considered a design challenge in itself. Hence, when exploring a viable problem space, it is important to explore which dilemmas form the most inspiring and relevant frame for guiding future design decisions. Here, choosing a dilemma can be fueled by generating ideas to address it and deciding whether to move on with or discard a dilemma based on its framing capacity in idea generation (Ozkaramanli, Desmet, & Ozcan, 2017). Exploring various dilemmas in this way will likely reveal clues about different aspects of the problem. Comparing the generated ideas will contribute to better understanding the larger problem space, making it possible to choose a frame in the form of a personal dilemma (cf. Dorst & Cross, 2001). The risk (for novice designers) here is to focus too much on the quality of the generated ideas, overlooking that the real intention is to explore the problem space so as to take a position in it. In that sense, dilemmas act mostly as a way-finding guide to sketch the context of the problem1.

Reflecting on personal dilemmas as frames

Foregrounding personal dilemmas in re-framing practices offers three main advantages. First, dealing with dilemmas can increase engagement with the problem space, and thus, may help avoid jumping to solutions prematurely. Everybody experiences dilemmas in everyday life. Therefore, giving a couple of dilemma examples to an audience is often sufficient to convey the main idea underlying the phenomenon and to invite people to contribute to the discussion with their own dilemmas. Second, dilemmas involve conflicting motivations or values, and such conflicts can trigger creative thinking (Benack, Basseches, & Swan, 1989): Once a particular dilemma is captured, the design team often almost immediately starts discussing design ideas. In the aforementioned dilemma example (Figure 1), for instance, lactation technologies (e.g. breast-pumps) can be designed in a way to productively deal with this dilemma. Third, dilemmas enable perspective taking. Identifying and articulating dilemmas necessitate comparing and contrasting the relationship between people’s goals and values, which helps being mindful about potential compromises that might otherwise remain implicit in frame creation (Ozkaramanli, Desmet, & Ozcan, 2017; also compare to Jonassen, 1997).

In a way, dilemmas both facilitate and complicate problem-framing, and this is their hidden virtue. Personal dilemmas form a helpful lens that can bridge multiple activities at the early, explorative stages of a design project (e.g. contextual research, problem-framing, idea generation). In this way, they offer a level of consistency to these activities: Designers actively seek to capture dilemmas in contextual research, elaborate on these dilemmas when exploring the problem space, and iteratively select and address multiple dilemmas through idea generation as a means to restrict alternatives and refine emerging frames. In addition, I argue that personal dilemmas embody a human-centered way of framing design problems. In other words, framing design problems as personal dilemmas (e.g. “I want to be a good mother” vs. “I want to have a flourishing career”) explicates the complexity of human experience and behavior through highlighting personal contradictions. On the other hand, finding dilemmas is not the same as finding problems. Although dilemmas and problems are similar concepts, they are not identical. Jonassen (2000, pp. 80-81) refers to dilemmas as the most ‘vexing’ type of ill-structured problems. This is why DDD requires not only asking ‘what’s wrong?’ in a design situation (i.e. finding a problem), but also ‘what’s right in the situation that we consider to be wrong?’ (i.e. finding a dilemma). This allows seeing ‘both sides of the coin’. In other words, DDD reveals that there is always a gain (e.g. mothers ensuring career prospects) that hides behind the loss represented by a problem (e.g. mothers stopping breastfeeding), and suggests that design can be best informed by the purposeful exploration of these gains and losses. Because of this, explicitly focusing on identifying dilemmas in problem-framing is likely to be a more onerous exercise than focusing solely on identifying problems.

In closing, this article mainly focused on personal dilemmas as DDD has so far mainly dealt with unpacking individual goals, emotions and choices. This is an invaluable resource for designing for experience. As design as a discipline moves towards dealing with complex societal challenges, interdisciplinary collaboration and thinking beyond individual goals and needs become increasingly important. In such design situations, wider societal perspectives, social dilemmas, and collaborative framing practices emerge. Design methods will need to evolve with this increasing complexity. Hence, how to ‘scale up’ the framing capacity of DDD by shifting its focus from individual experiences to societal challenges is a core research question for the future. Noteworthy here is that dilemmas are not limited to intra-personal (i.e. within-person) dilemmas, but also exist as inter-personal (i.e. between people) dilemmas and conceptual dilemmas (Ozkaramanli, 2021). This distinction is significant for complex multi-stakeholder settings, as dilemmas among various stakeholders may be valuable entry points to collective reflection and perspective-taking (e.g. Castaño et al., 2017). Although dilemmas may create discomfort and dissent in such settings, I propose that, rather than trying to disregard or disguise dilemmas, we should encourage their articulation and negotiation as an authentic framing practice.