Use of types of justifications in everyday, scientific, and pseudo-scientific contexts

Downloads

- PDF (Español (España)) 698

- EPUB (Español (España)) 78

- VISOR (Español (España))

- MÓVIL (Español (España))

- XML (Español (España)) 95

DOI

https://doi.org/10.25267/Rev_Eureka_ensen_divulg_cienc.2024.v21.i2.2102Info

Abstract

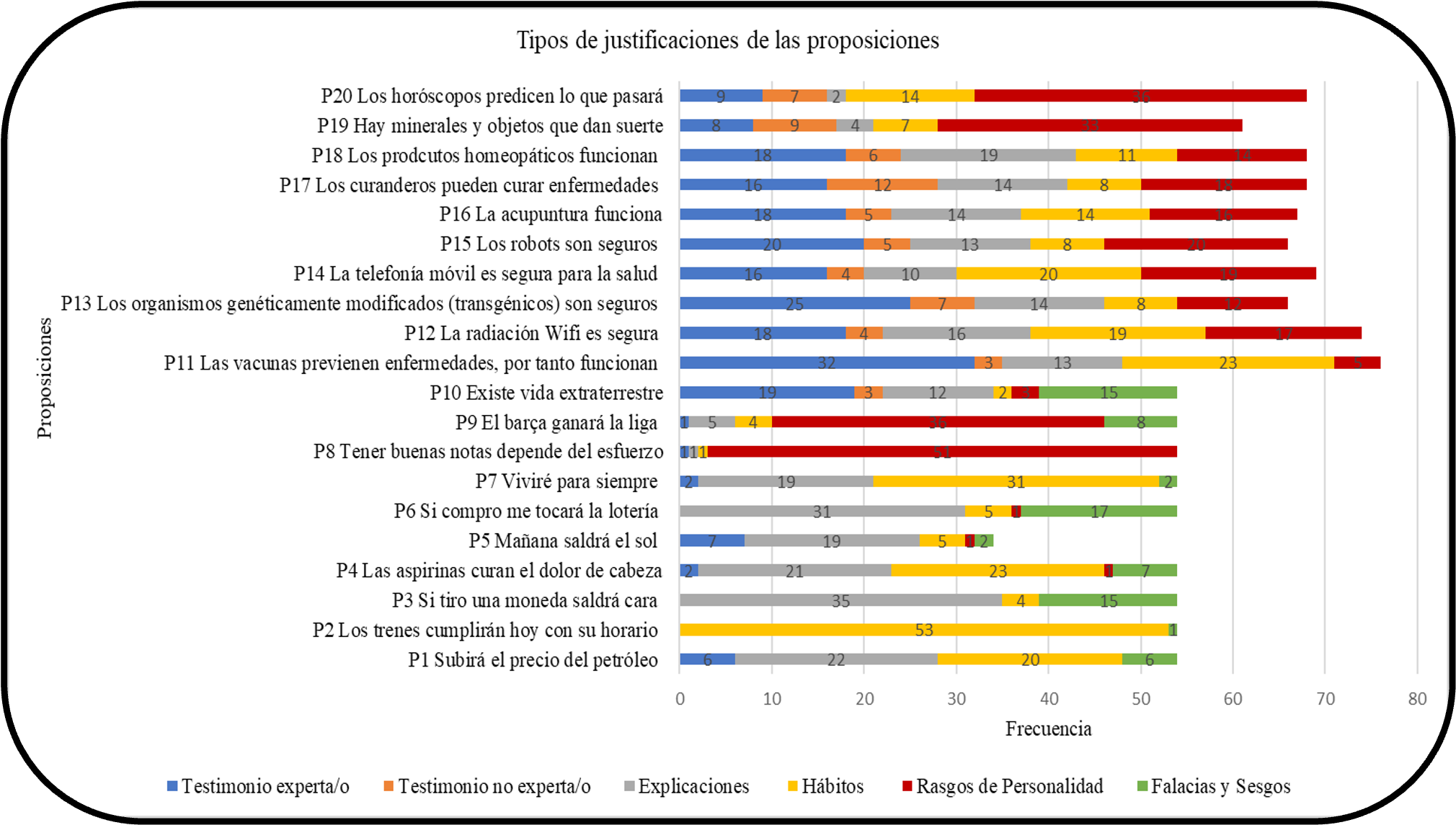

This paper studies how students justify everyday, scientific, and pseudo-scientific propositions, and whether they recognize the type of justifications they use. For this purpose, we work with 54 students in the 3rd year of compulsory secondary education in the subject of biology and geology, in which two learning activities designed to work on the evaluation of propositions are implemented. The results provide information on the students' preference for using habits and explanations in the evaluation of everyday propositions, and expert testimony and personality traits in the evaluation of scientific and pseudoscientific propositions, as well as the inability to acknowledge explanations and personality traits. These results provide us with useful background for reflecting on how to work on epistemic cognition in the classroom and thus broaden the conceptual frameworks on epistemic cognition.

Keywords

Downloads

Supporting Agencies

How to Cite

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Sonia Carolina Sepúlveda González, Anna Marbà Tallada , Jordi Domènech Casal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Require authors to agree to Copyright Notice as part of the submission process. This allow the / o authors / is non-commercial use of the work, including the right to place it in an open access archive. In addition, Creative Commons is available on flexible copyright licenses (Creative Commons).

Reconocimiento-NoComercial

CC BY-NC

References

Aikenhead, G. S. (2005). Science‐based occupations and the science curriculum: Concepts of evidence. Science Education, 89(2), 242-275.

Anderson, J., y Rainie, L. (2017). The future of truth and misinformation Online. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/10/19/the-future-of-truth-and-misinformation-online

Barzilai, S., y Chinn, C. A. (2018). On the Goals of Epistemic Education: Promoting Apt Epistemic Performance. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 27(3), 353-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1392968

Bokros, S. E. (2021). A deference model of epistemic authority. Synthese, 198(12), 12041–12069. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11229-020-02849-Z

Bradley, R. (2018). Learning from others: conditioning versus averaging. Theory, 85, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-017-9615

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) (2023). Barómetro marzo. https://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-archivos/Marginales/3380_3399/3398/es3398mar.pdf

Chalmers, A. F. (2010). ¿Qué es esa cosa llamada ciencia? Siglo XXI.

Chinn, C. A., y Rinehart, R. W. (2016). Epistemic cognition and philosophy: Developing a new framework for epistemic cognition. En Greene, J. A., Sandoval, W. A., and Braten, I. (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic cognition (pp. 460-478). Routledge.

Chinn, C. A., Buckland, L. A., y Samarapungavan, A. (2011). Expanding the dimensions of epistemic cognition: Arguments from philosophy and psychology. Educational Psychologist, 46(3), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.587722

Chinn, C. A., Rinehart, R. W., y Buckland, L. A. (2014). Epistemic cognition and evaluating information: Applying the AIR model of epistemic cognition. En D. Rapp and J. Braasch (Eds.), Processing inaccurate information: Theoretical and applied perspectives from cognitive science and the educational sciences (pp. 425-453). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chinn, C. A., Yoon, S. A., Hussain-Abidi, H., Hunkar, K., Noushad, N. F., Cottone, A. M., y Richman, T. (2023). Designing learning environments to promote competent lay engagement with science. European Journal of Education, 58(3), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/EJED.12573

Davidson, R. J., y Begley, S. (2012). El perfil emocional de tu cerebro. (Vol. 225). Grupo Planeta.

Domènech-Casal, J. (2019). Escalas de certidumbre y balanzas de argumentos. Una experiencia de construcción de marcos epistemológicos para el trabajo con Pseudociencias en secundaria. Ápice. Revista de Educación Científica, 3(2), 37-53. https://doi.org/10.17979/arec.2019.3.2.4930

Domènech-Casal, J. y Marbà-Tallada, A. (2022). La dimensión epistémica de la competencia científica. Ejes para el diseño de actividades de aula. Didáctica de Las Ciencias Experimentales y Sociales, 0(42), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.7203/DCES.42.21070

Fadel, Ch., Bialik, M y Trilling, B. (2016). Educación en cuatro dimensiones: las competencias que los estudiantes necesitan para su realización. Centro de Innovación en Educación de Fundación de Chile. https://www.centroderecursos.educarchile.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12246/55866/charles-fadel-educacion-en-cuatro-dimensiones.pdf

FECyT (2023). 11.ª Encuesta percepción social de la ciencia y la tecnología -2022. Informe completo. https://www.fecyt.es/es/noticia/encuestas-de-percepcion-social-de-la-ciencia-y-la-tecnologia-en-espana

Fischer, G. N. (1990). Psicología social: conceptos fundamentales. Narcea.

Fisher, M., y Keil, F. C. (2014). The illusion of argument justification. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(1), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0032234

Greene, J. A., Azevedo, R., y Torney-Purta, J. (2008). Modeling epistemic and ontological cognition: Philosophical perspectives and methodological directions. Educational Psychologist, 43(3), 142-160.

Greene, J. A., Chinn, C. A., y Deekens, V. M. (2021). Experts’ reasoning about the replication crisis: Apt epistemic performance and actor-oriented transfer. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 30(3), 351-400.

Greene, J. A., y Yu, S. B. (2016). Educating critical thinkers: The role of epistemic cognition. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 45-53.

Greño, H. M. (2019). Nuestra mente nos engaña: sesgos y errores cognitivos que todos cometemos. Shackleton books.

Hofer, B. K., y Pintrich, P. R. (1997). The Development of Epistemological Theories: Beliefs about Knowledge and Knowing and Their Relation to Learning. Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170620

INE (2022). Encuesta sobre Equipamiento y Uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en los Hogares. https://ine.es/prensa/tich_2022.pdf

Iordanou, K. (2016). From Theory of Mind to Epistemic Cognition. A Lifespan perspective. Frontline Learning Research, 4(5), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.14786/FLR.V4I5.252

Jiménez-Aleixandre, M. P. (2010). 10 ideas clave. Competencias en argumentación y uso de pruebas (Vol. 12). Graó.

Kahneman, D. (2003). Mapas de racionalidad limitada: psicología para una economía conductual. Discurso pronunciado en el acto de entrega del premio Nobel de Economía 2002. RAE: Revista Asturiana de Economía, 28, 181–225.

Kahneman, D. (2012). Pensar rápido, pensar despacio. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, S. A. U.

Keren, A. (2007). Epistemic Authority, Testimony, and the Transmission of Knowledge. Episteme, 4(3), 368–381. https://doi.org/10.3366/E1742360007000147

Keren, A. (2018). The public understanding of what? Laypersons’ epistemic needs, the division of cognitive labor, and the demarcation of science. Philosophy of Science, 85(5), 781-792. https://doi.org/10.1086/699690

Kind, P., y Osborne, J. (2017). Styles of Scientific Reasoning: A Cultural Rationale for Science Education? Science Education, 101(1), 8–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/SCE.21251

Kuhn, D. (2001). How do people know? Psychological Science, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00302

Kuhn, D., y Iordanou, K. (2022). Why Do People Argue Past One Another Rather than with One Another? Reason, Bias, and Inquiry, 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/OSO/9780197636916.003.0015

Lipman, M. (2016). El lugar del pensamiento en la educación: Textos de Matthew Lipman. Ediciones Octaedro.

National Research Council. (2012). A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13165

Núñez Ladevéze, L., Núñez Canal, M., y Irisarri Núñez, J. A. (2017). Normative affectivity as the foundation of domestic authority in the digital society. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, 331–348. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2017-1168

Nussbaum, M. C. (2008). Paisajes del pensamiento: la inteligencia de las emociones. Paidós.

Ogborn, J., Kress, G., Martins, I. y McGillicuddy, K. (1998). Formas de explicar: la enseñanza de las ciencias en secundaria. Aula XXI-Santillana.

Osborne, J. F., y Patterson, A. (2011). Scientific argument and explanation: A necessary distinction? Science Education, 95(4), 627-638.

Quarderer, N. A., Fulmer, G. W., Hand, B., y Neal, T. A. (2021). Unpacking the connections between 8th graders' climate literacy and epistemic cognition. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 58(10), 1527–1556. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21717

Sadler, T. D. (2004). Informal reasoning regarding socioscientific issues: A critical review of research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(5), 513–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20009

Stanovich, K. E. (2010). Decision making and rationality in the modern world. Oxford University Press.

Steup, Matthias and Ram Neta, Epistemology, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/epistemology

Wei, L., Firetto, C. M., Duke, R. F., Greene, J. A., y Murphy, P. K. (2021). High school students’ epistemic cognition and argumentation practices during small-group quality talk discussions in science. Education Sciences, 11(10), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100616

Zagzebski, L. T. (2012). Epistemic authority: A theory of trust, authority, and autonomy in belief. Oxford University Press.

Zetterqvist, A., y Bach, F. (2023). Epistemic knowledge–a vital part of scientific literacy? International Journal of Science Education, 45(6), 484-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2023.2166372